Episode 20: Martha Clarke

Originally recorded and released as Lady’s After Hours podcast, for Lady.

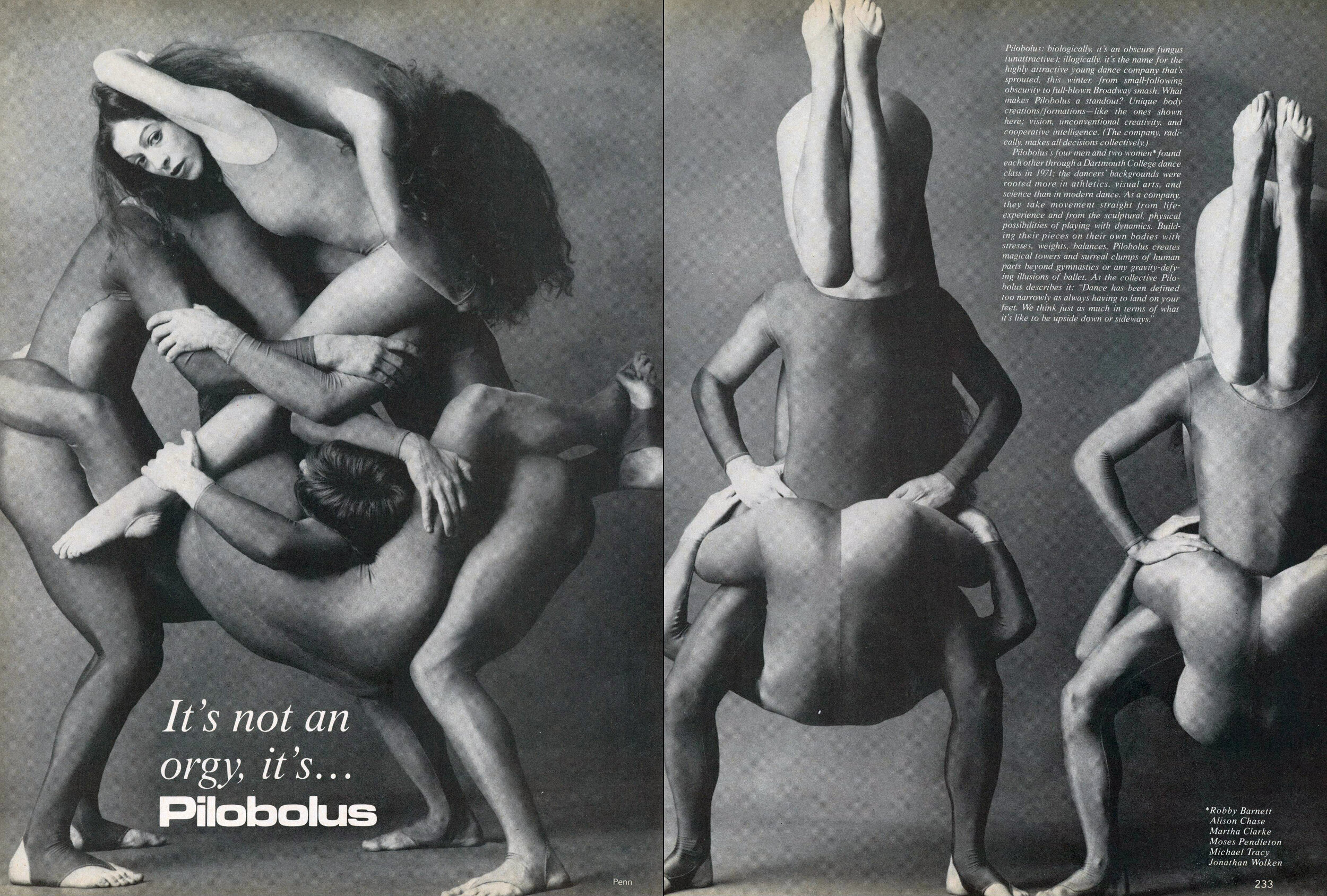

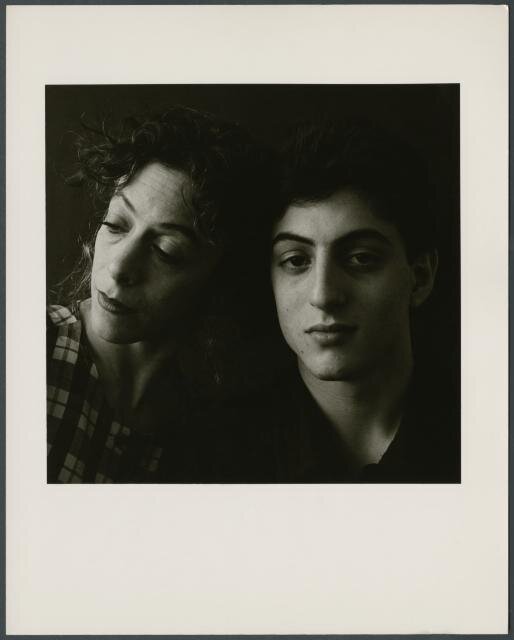

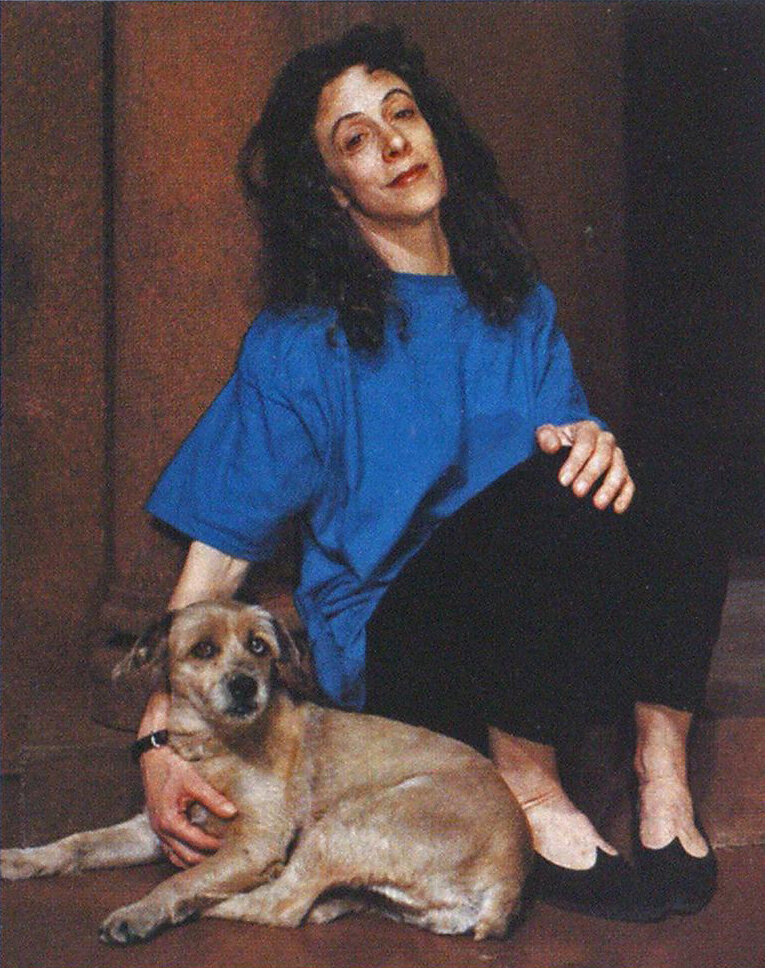

Martha (L) performing ‘Untitled’ with Alison Chase as part of Pilobolus.

So much has changed since this interview was recorded in February 2020. While it feels like a completely other time—a different world—everything in this conversation is still valid and has possibly taken on even greater importance. When I spent most of a snowy Saturday at Martha Clarke’s home in Connecticut I knew that all the subjects we touched on were so interesting, so vital—the creative process, growing older, the difficulties of raising money and surviving in the arts as an older woman, the current administration’s devaluation of the arts, death—but now, three months later, I can genuinely say that these themes were prescient. How will the arts emerge from this pandemic? How will artists and creatives support themselves when so many institutions have gone bankrupt and there is no money for grants? What gems and masterworks will be lost forever, never coming to total fruition?

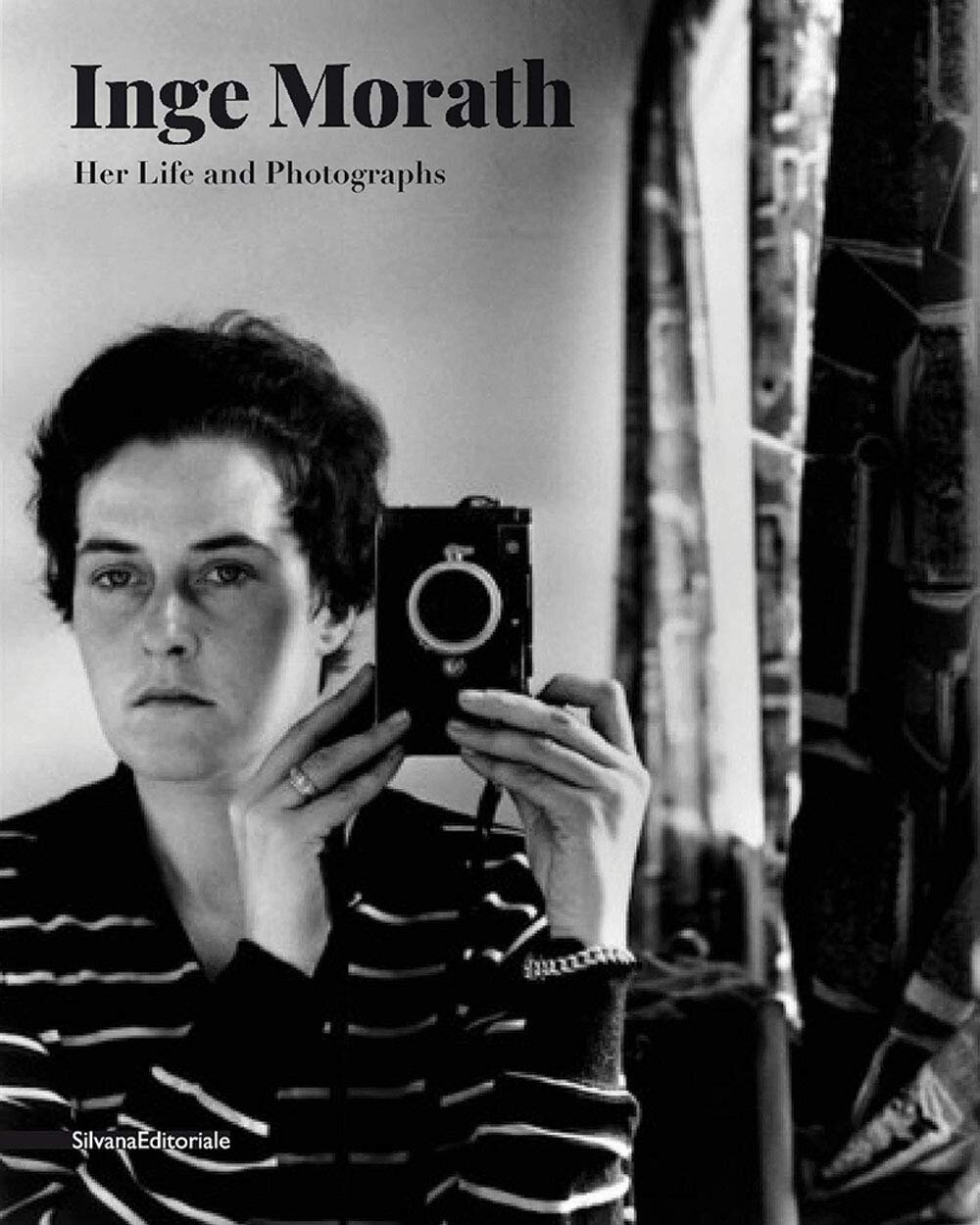

Martha Clarke is a dancer, choreographer, director—transcending dance and theater to make deeply evocative moving spectacles of beauty steeped in history. For the last thirty years she has lived in an early nineteenth-century farmhouse that was previously owned by the artist Arshile Gorky, who converted it into a painting studio featuring a two-story window wall in the 1940s. Bathed in the most miraculous light are Martha’s antiques, collected during her travels all over the world. We spent several hours recording this podcast episode at her rough-hewn farmhouse table, where she openly shared her memories, thoughts and feelings. I write these short bios as little introductions to the people I interview—hopefully drawing you in and making you eager to listen to their own words, as the real meat is in the conversations.

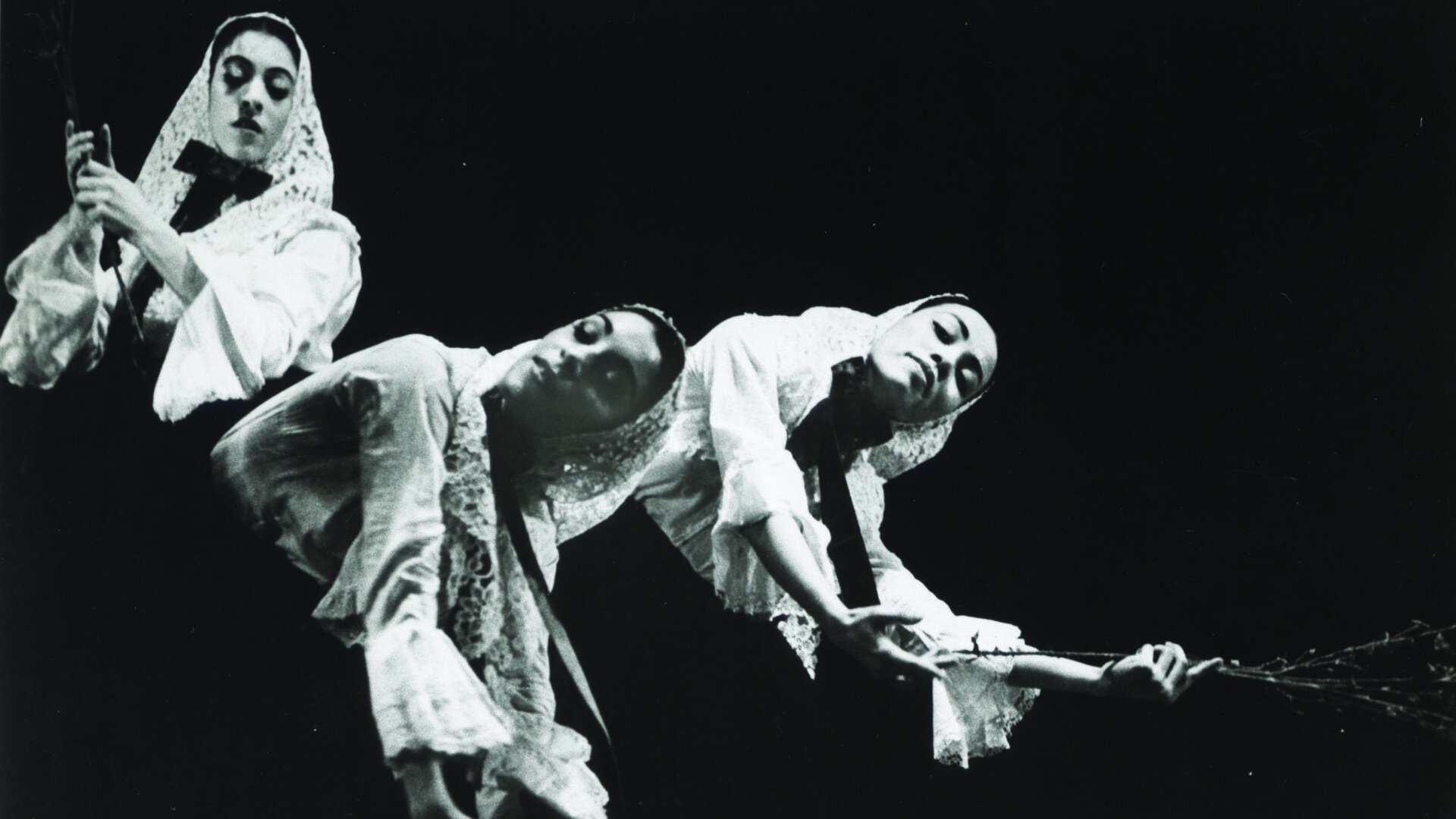

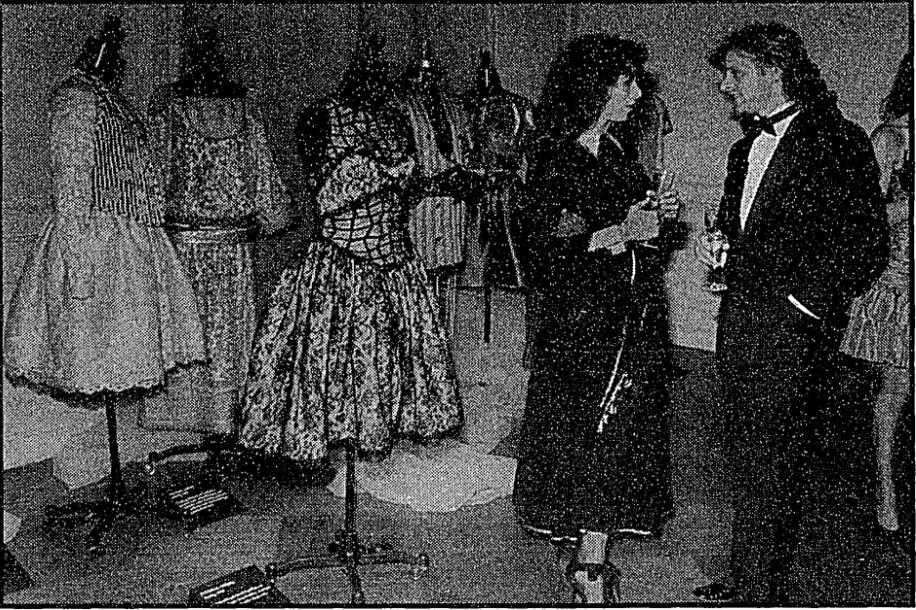

Vienna: Lusthaus, 1986.

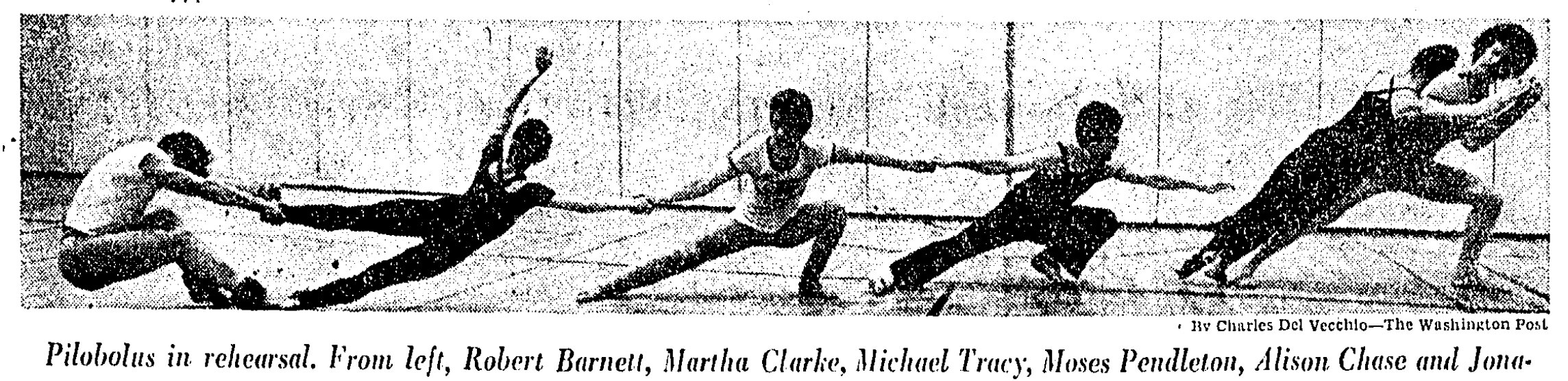

From Baltimore, Clarke began dancing as a child at the Peabody Preparatory Department – first in ballet and then modern dance. A natural dancer, due to her talents she grew up at an escalated pace. Clarke summered at the American Dance Festival as a teenager, started studying at Julliard at 17, danced as part of Anna Sokolow’s company, got married at twenty to the sculptor Philip Grausman, moved to Rome, had a baby and gave up dance for five years. In 1971 Grausman was invited to be artist-in-residence at Dartmouth College, where Clarke met the head of the dance program, Alison Chase, and a group of young male athletes who had recently fallen in love with dance under Chase’s tutelage. Forming their own dance troupe, named Pilobolus after a type of mushroom, the four jocks invited Chase and Clark to join their new endeavor—a highly athletic, sculptural form of movement.

Miracolo d’amore, 1987-88.

Pilobolus was an instant success in the dance world and the troupe were soon traveling the world with Clark’s child in tow. In the interview Martha talks openly about the ups and downs of Pilobolus, which is still in existence today, and her own emerging creativity that led her to leave the group at the end of the decade. In 1979 she formed her own dance company, Crowsnest, alongside Felix Blaska and her Pilobolus partner Robert Barnett. Joyce Chopra documented Martha’s process of creating her first solo dances in the film Martha Clarke: Light & Dark. A Dancer’s Journal (1981). Away from Pilobolus Clarke’s work became more historical—mining references from all different eras, she found influences in paintings, photographs, historical periods, and literature. One particularly evocative dance, Nocturne, drew inspiration from a photograph by Baron de Meyer and centered on an elderly dancer reliving her balletic glory days. Her work also began to straddle dance and theater, an intersection that confused the critics but one that allowed her creativity to blossom. In 1990 Michael Feingold, a theatre critic for the Village Voice, said of Clarke: “She is non-imitable. She doesn’t deal in the conventions of performance art, although she is most at ease with the physical vocabulary of dance, she is really about image theater.”

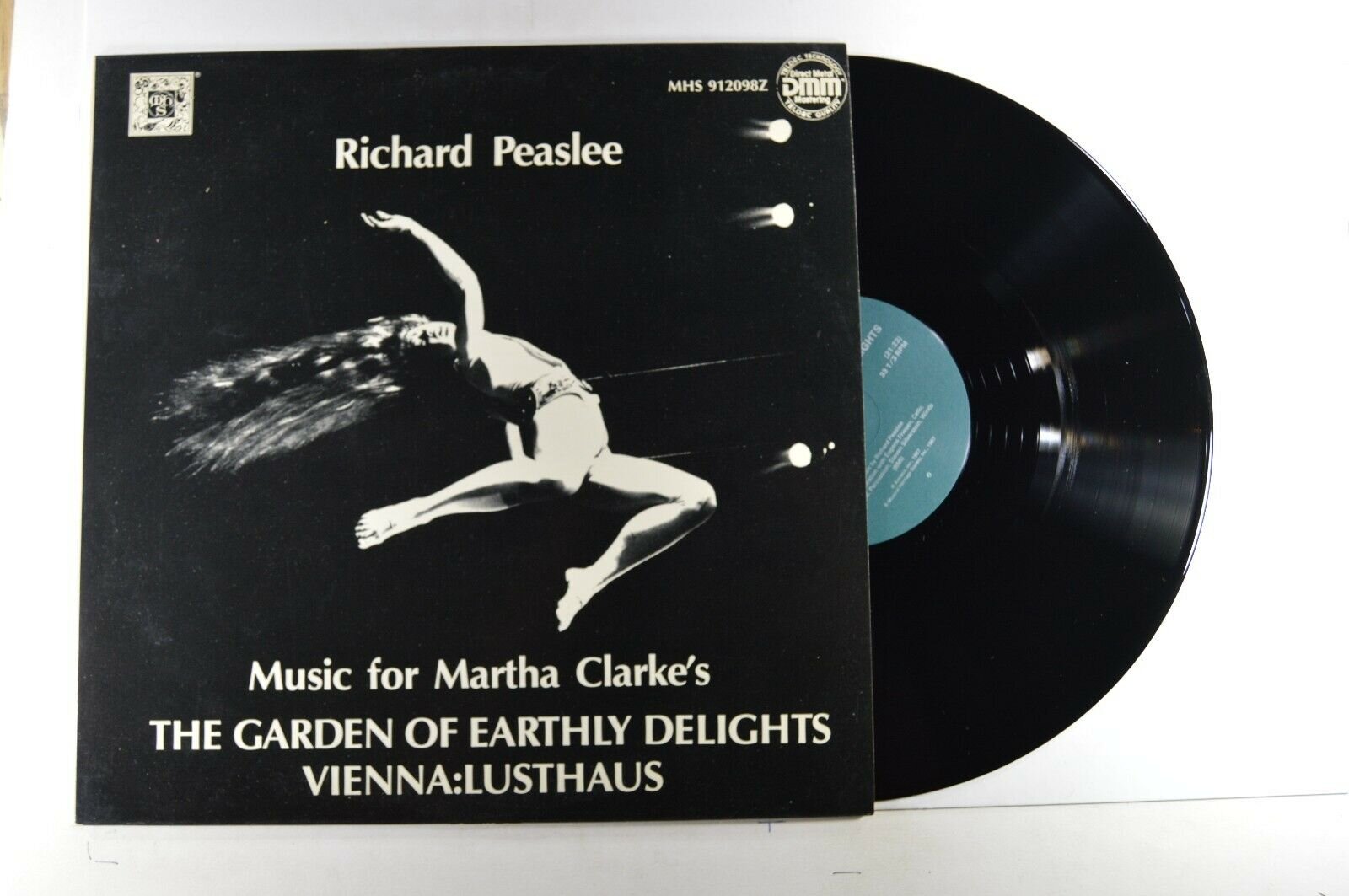

Recreating Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490 – 1510) as a phantasmagoric exploration of theatre, dance, music and flying in 1984 brought Clarke both critical and commercial success. Her following works explored such themes as Vienna at the fin de siècle (Vienna: Lusthaus, 1986) and erotic love (Miracolo d’amore, 1987-88). Two of her works have drawn from Kafka—A Metamorphosis in Miniature (1982), a performance art piece with actress Linda Hunt of his novella The Metamorphosis, and The Hunger Artist (1987), about the life of the writer. What marks all of these works is their dreamlike quality—nonlinear, they are more sketches of ideas than plotted story. They invite the viewer into an illusory world of fantasy. Some have been more successful than others—as you’ll hear us discuss, Endangered Species in 1990 was her first real artistic and commercial failure. Too large in scale and in scope, Clarke took on too much—set to the words of Walt Whitman, the cast included an elephant and dealt with themes of domination, extinction, race, and war (clips from Hitler speeches were included in the soundtrack, alongside opera music and jungle sounds). Endangered Species was pulled from the Brooklyn Academy of Music before it finished its run; marking a crucial transition in Clarke’s career. Though she had earlier that year won a MacArthur genius grant, Martha now lacked confidence in her own ideas so took to interpreting other people’s work and began to direct operas and plays—Mozart’s operas The Magic Flute in 1992 and Cosi Fan Tutte at Glimmerglass in 1993 and a theatre piece on Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures Underground (1994). Clarke returned to original full-length productions with Dammerung in 1995. Over the following years she would direct many other operas and productions (including directing an opera on Marco Polo by the Chinese composer Tan Dun), in addition to the creation of her own projects.

My first introduction to Clarke’s work was her adaptation of Colette’s 1920 novella Chéri, performed at the Signature Theater in NYC in 2013. A tragedy of forbidden love between a young man and an older woman set in Belle Époque Paris, the fusion of dance and theater (with a narration spoken by Amy Irving) was captivating to me. Three years later I returned to the Signature for Angel Reapers, a dance-theater piece about the Shakers that she created with writer Alfred Uhry. Based on actual Shaker movements and songs, it was spellbinding—a vivid spiritual portrait of a people and their beliefs.

Endangered species, 1990.

In many ways it was Clarke’s intriguing way of blending a multitude of ideas and inspirations into the creation of a multimedia dream world that seeded my desire to interview her. The creative process—the why’s, the how’s, the research, the false starts, the edits, the reworking—captivates me, and I wanted to know how she works, how she researches, how she coalesces her ideas into a finished whole. Also, what affect her personal life had on these decisions and her projects—I came across a 1990 interview in which she stated, “I guess, in a way, my work is really about the realm of dreams. It has been a way to discipline my devils, get one’s snakes out of their lair and make sense of them.” As she revealed in our conversation, the ties between her private world and the stage were often psychologically quite tight. Her marriage fell apart in the early 1980s due to an affair that would become a tempestuous relationship—and fodder for many of her most important works.

For the last few years Clarke has been working on a project about St. Francis of Assisi, in addition to two other projects. Tellingly this process has unveiled to her the ageism inherent in the world of performance grants. Now 75 Martha finds herself often excluded, overlooked or pushed to the side as the producers and foundations seek out young, new talent—forgetting the wisdom found in our elders. This part of our conversation feels very prophetic in light of a pandemic that attacks the elderly and the often-callous way that this demographic has been discussed by governments and the media. We also spoke of the loneliness inherent in growing old, when one-by-one you lose those closest to you. Right before this interview took place Martha’s cousin, the producer Margo Lion, passed away, and in the time following she lost her brother. The frailty and shortness of life—a subject often explored in Clarke’s dances—writ large, both in the personal and on a global scale.

While there is much more I could write about her, our podcast interview stands as both a wonderful introduction to Martha Clarke as well as an in-depth exploration into her remarkable life and oeuvre. Marriage, love, children, family, friendships, and collaborative working relationships—she spoke openly about all of these subjects, in addition to elucidating her creative process and the meanings behind her works.