Episode 39: Allen Jones

Last year I started a Substack newsletter, also called Sighs and Whispers, which covers many of the same themes as this podcast. You should sign up! I send out one free newsletter a week and one paid—all financial support of the newsletter allows me the time to write the newsletter, make this podcast, and do my Instagram, so please do consider becoming a paid subscriber.

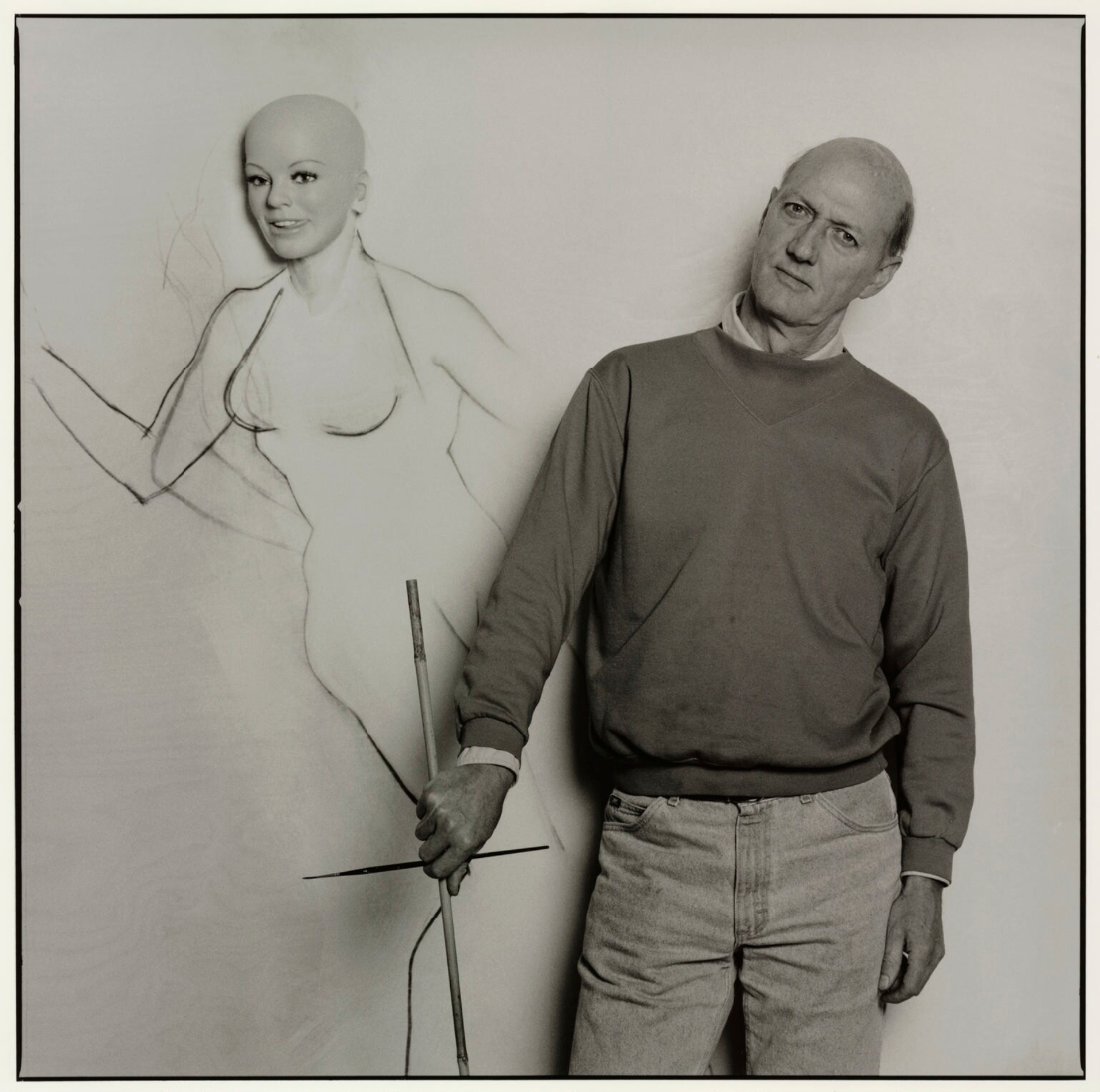

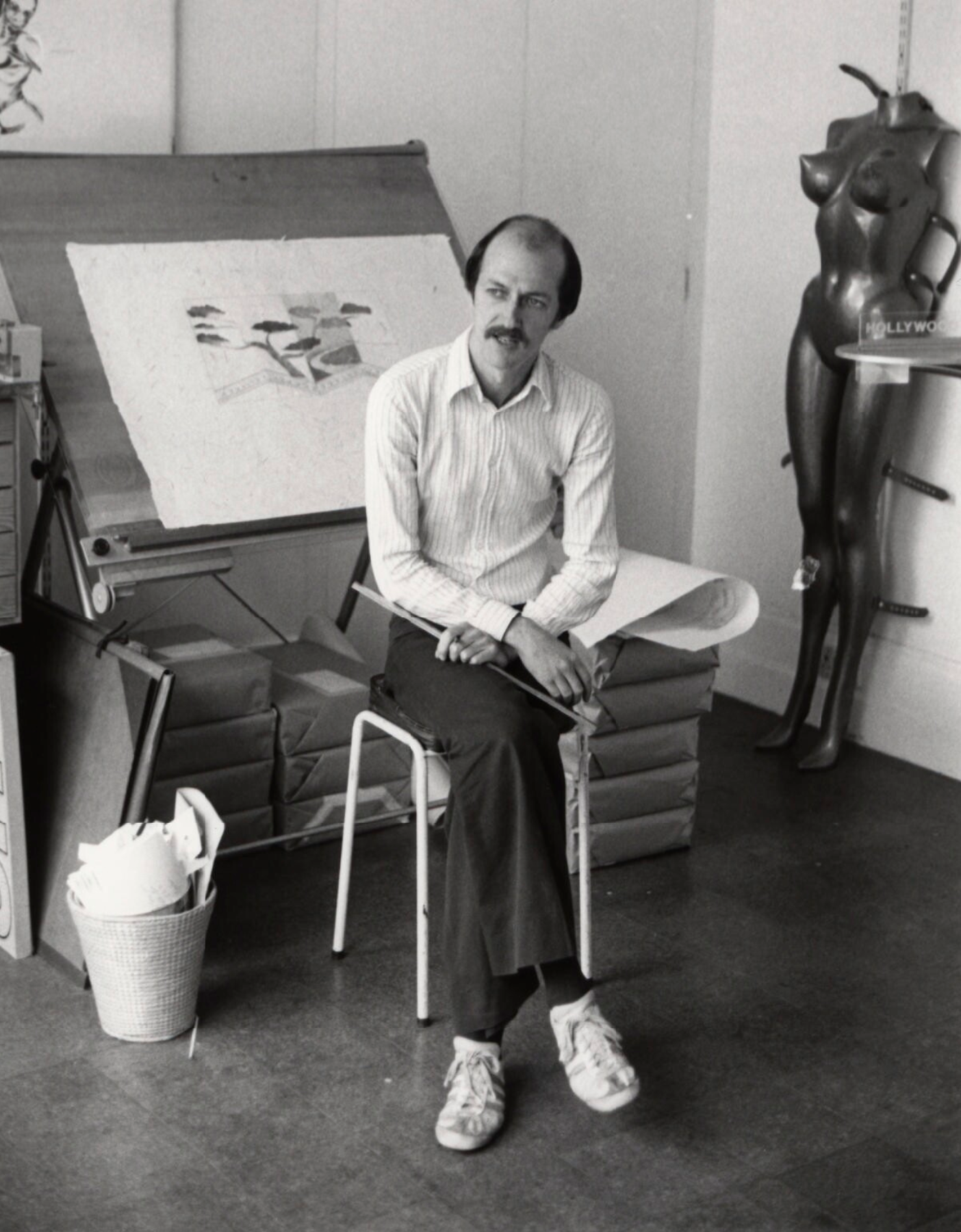

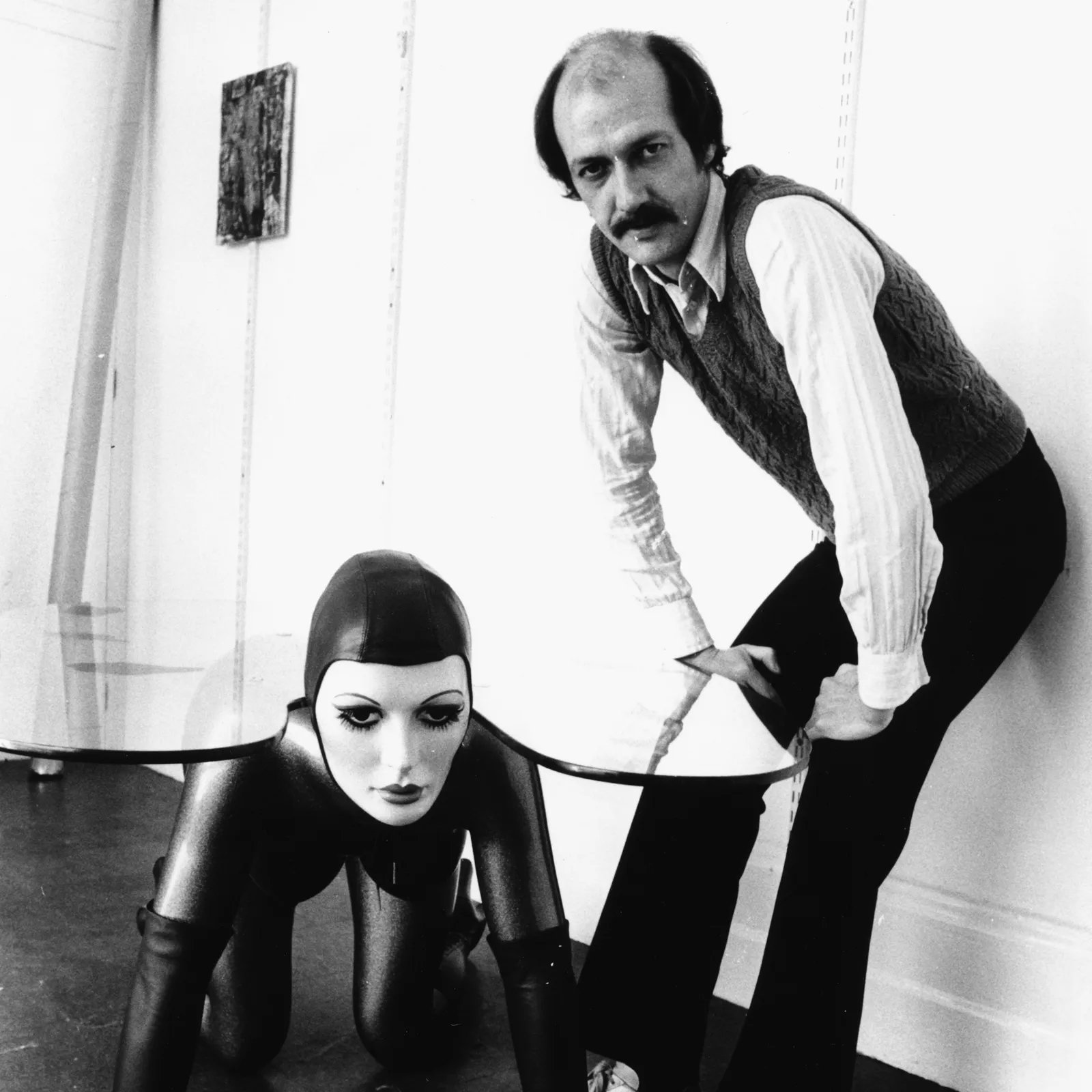

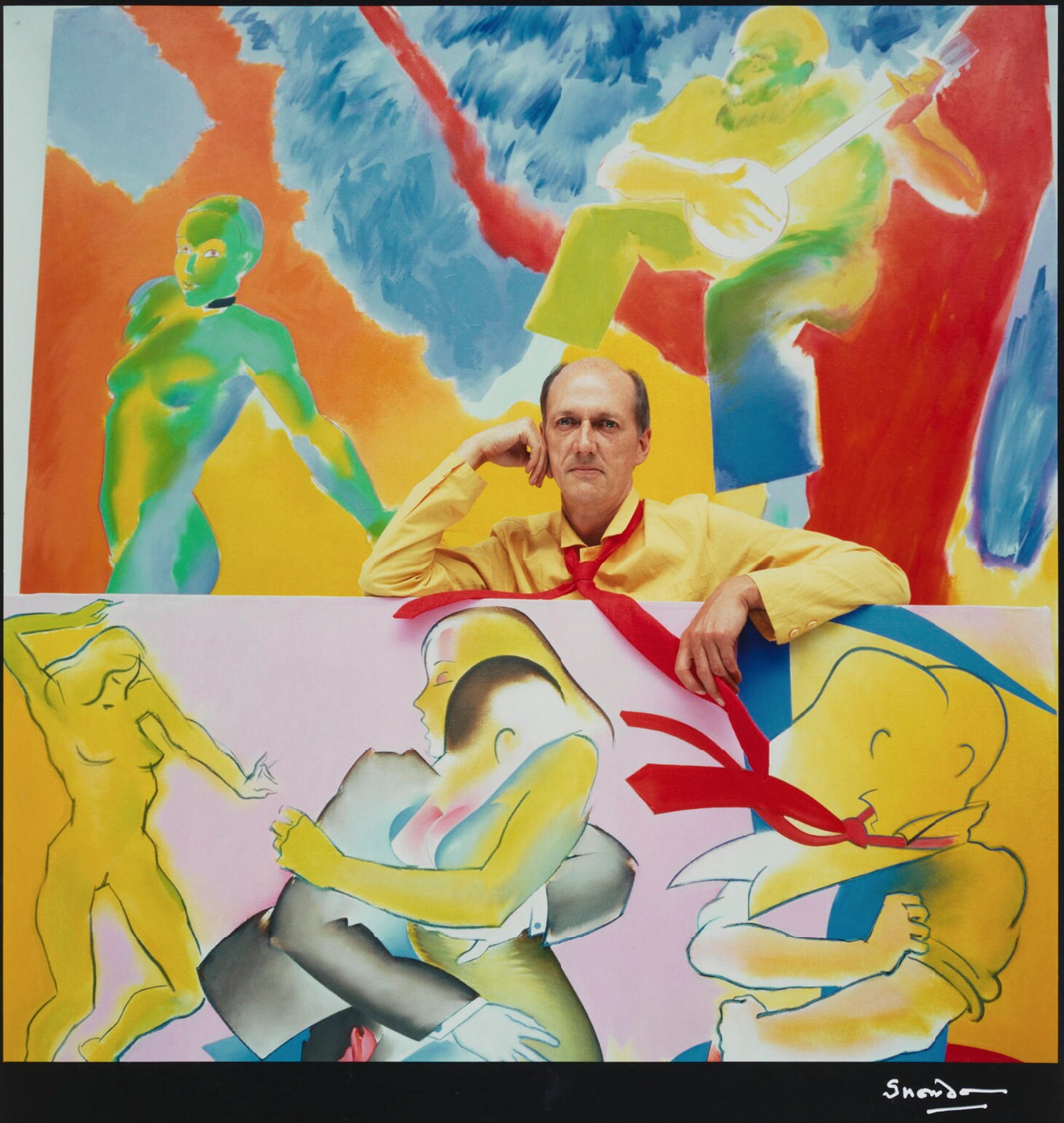

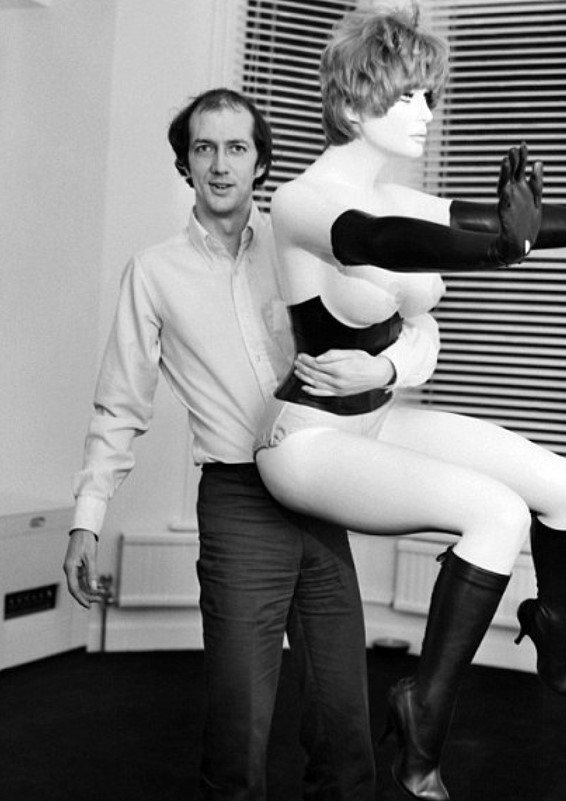

Allen Jones. Portrait by Eamonn McCabe, 2015.

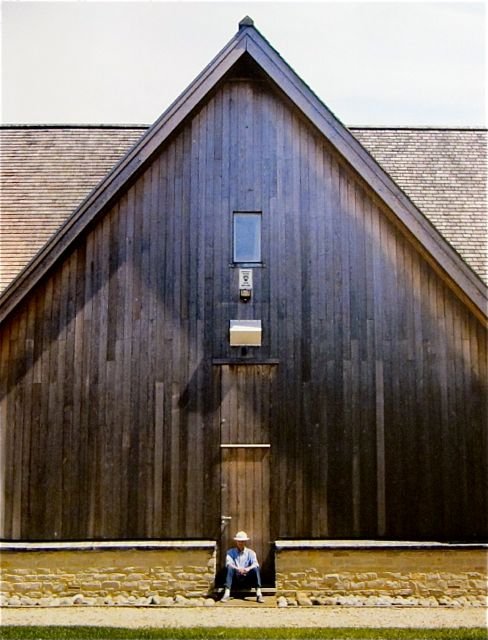

In February I flew to London, and on my first day—very jetlagged—I took a train out to Oxfordshire to meet pop artist, painter and sculptor Allen Jones at his rural home and studio. One of Britain’s most famous living artists, at 85, he continues to paint everyday day in his large barn-like studio in the beautiful English countryside.

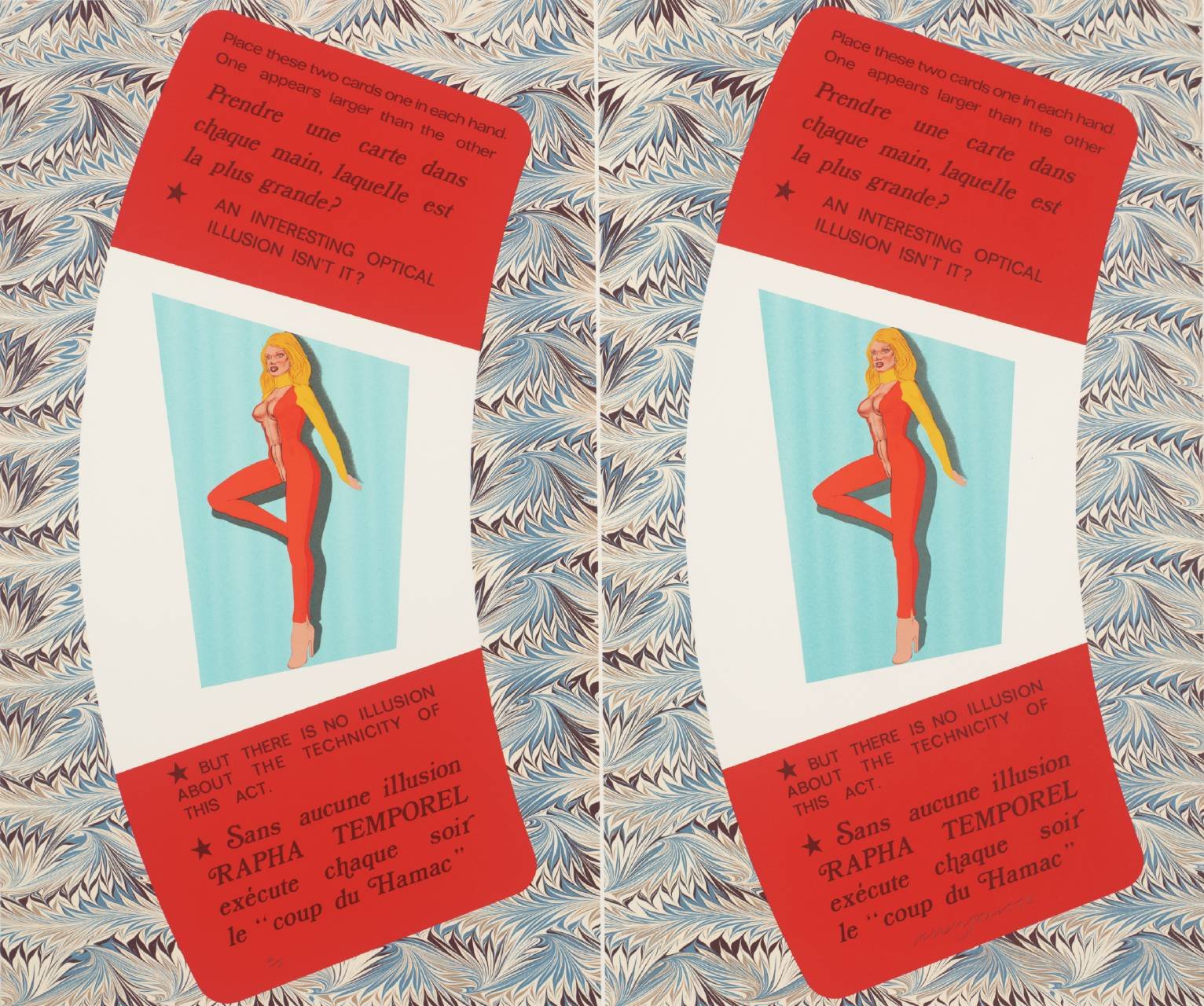

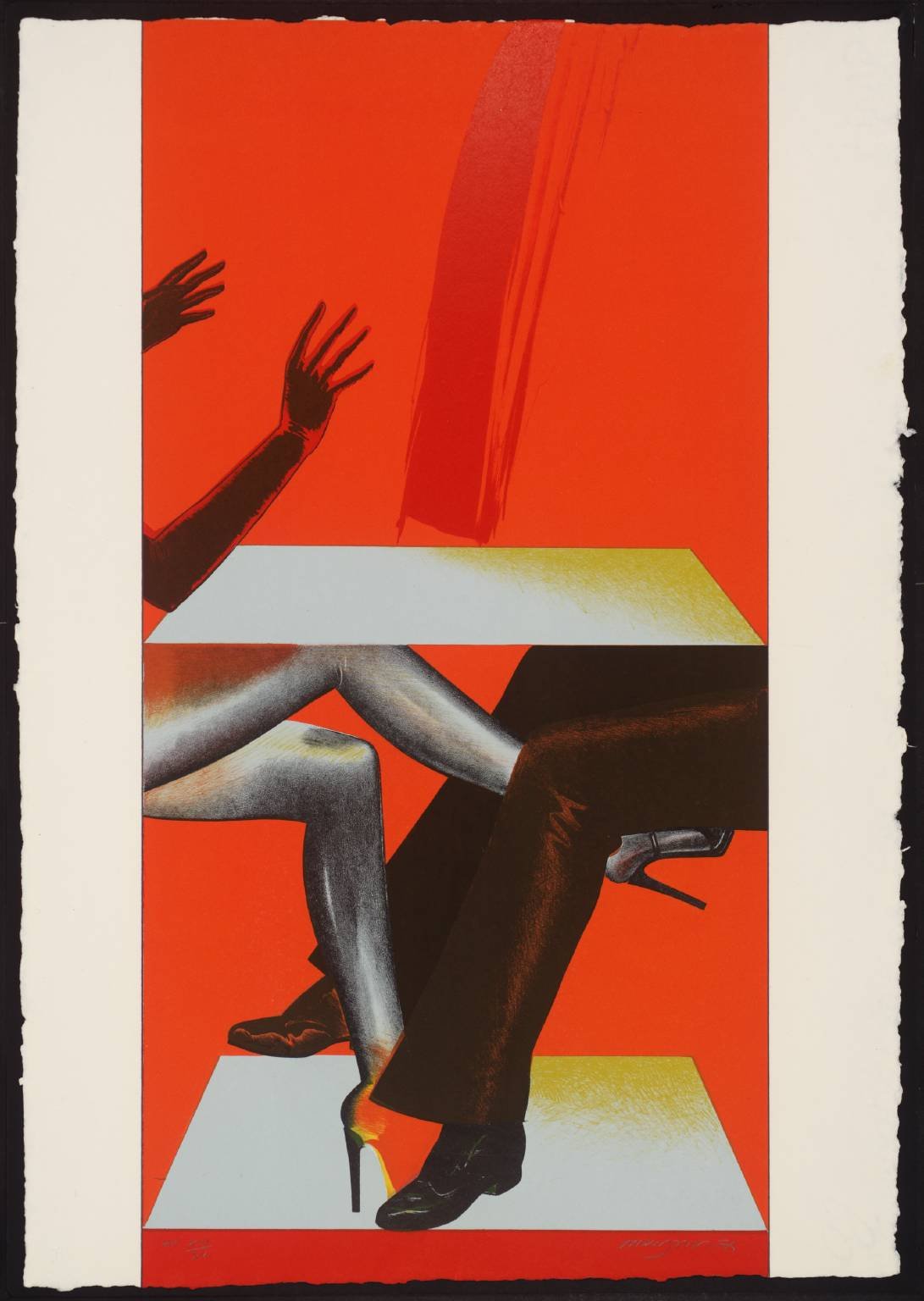

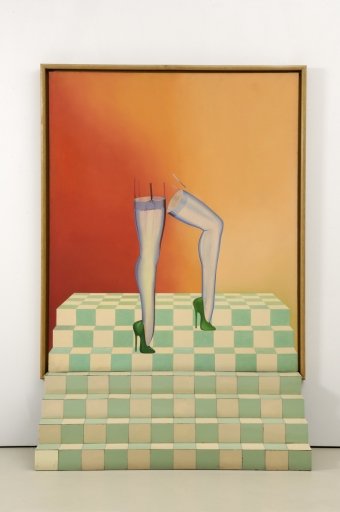

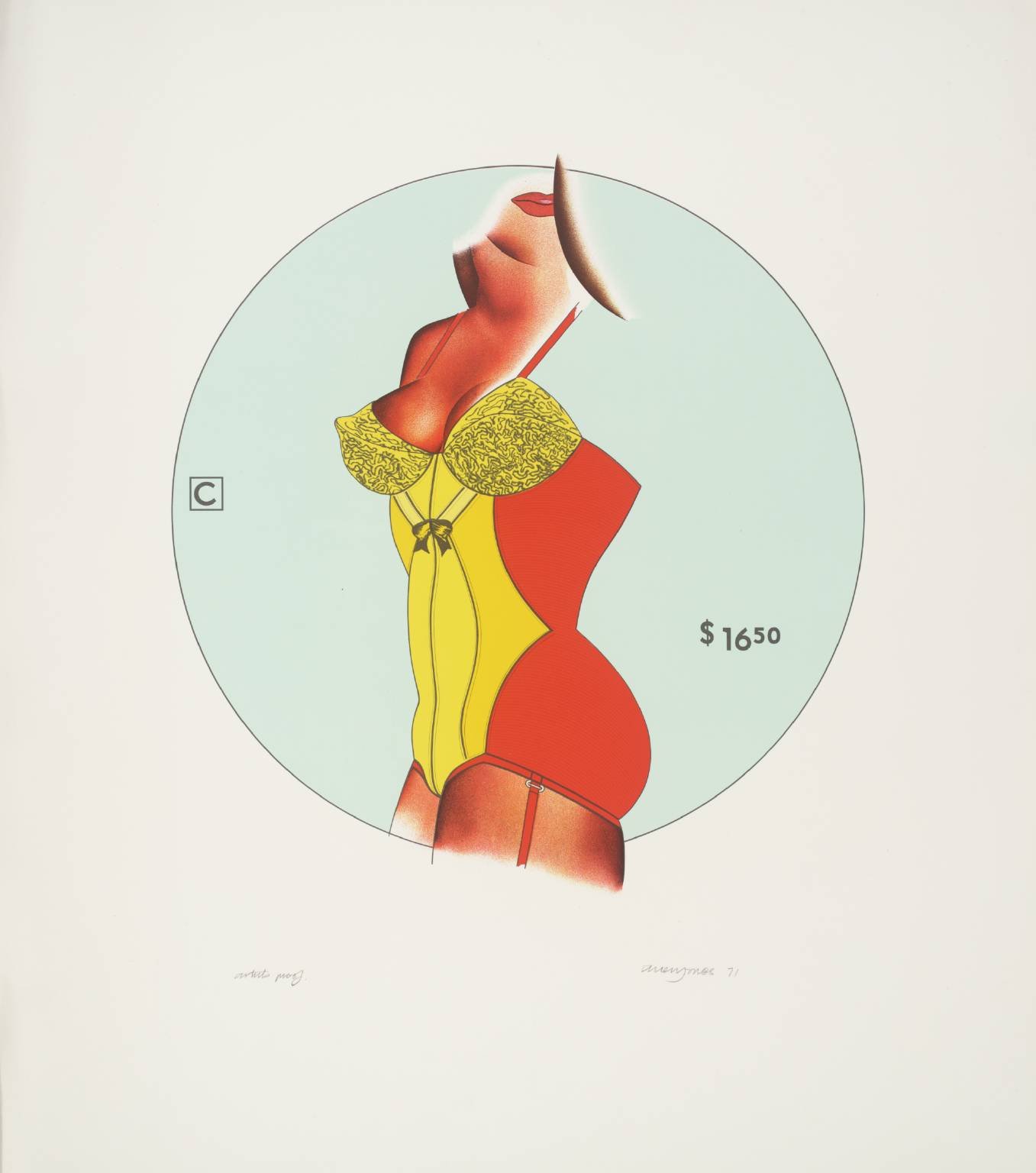

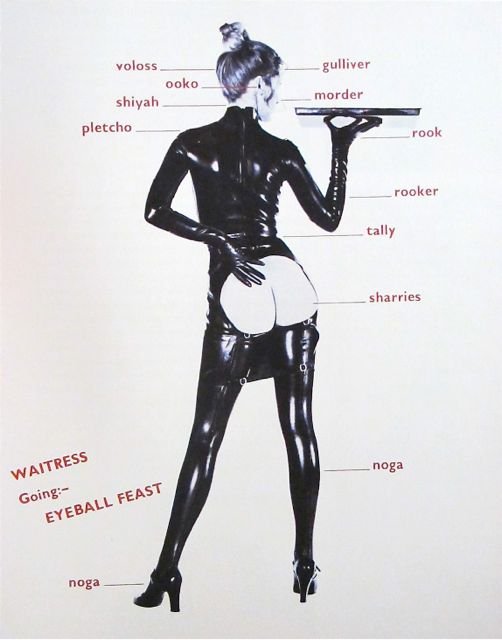

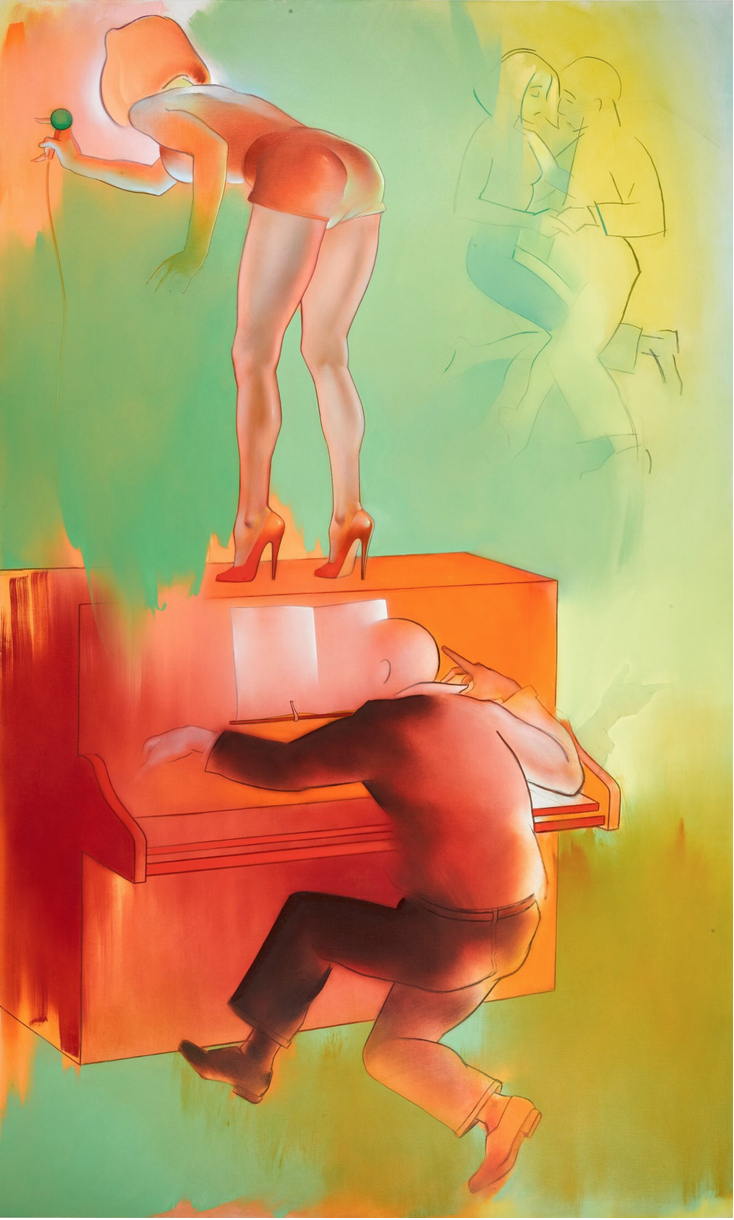

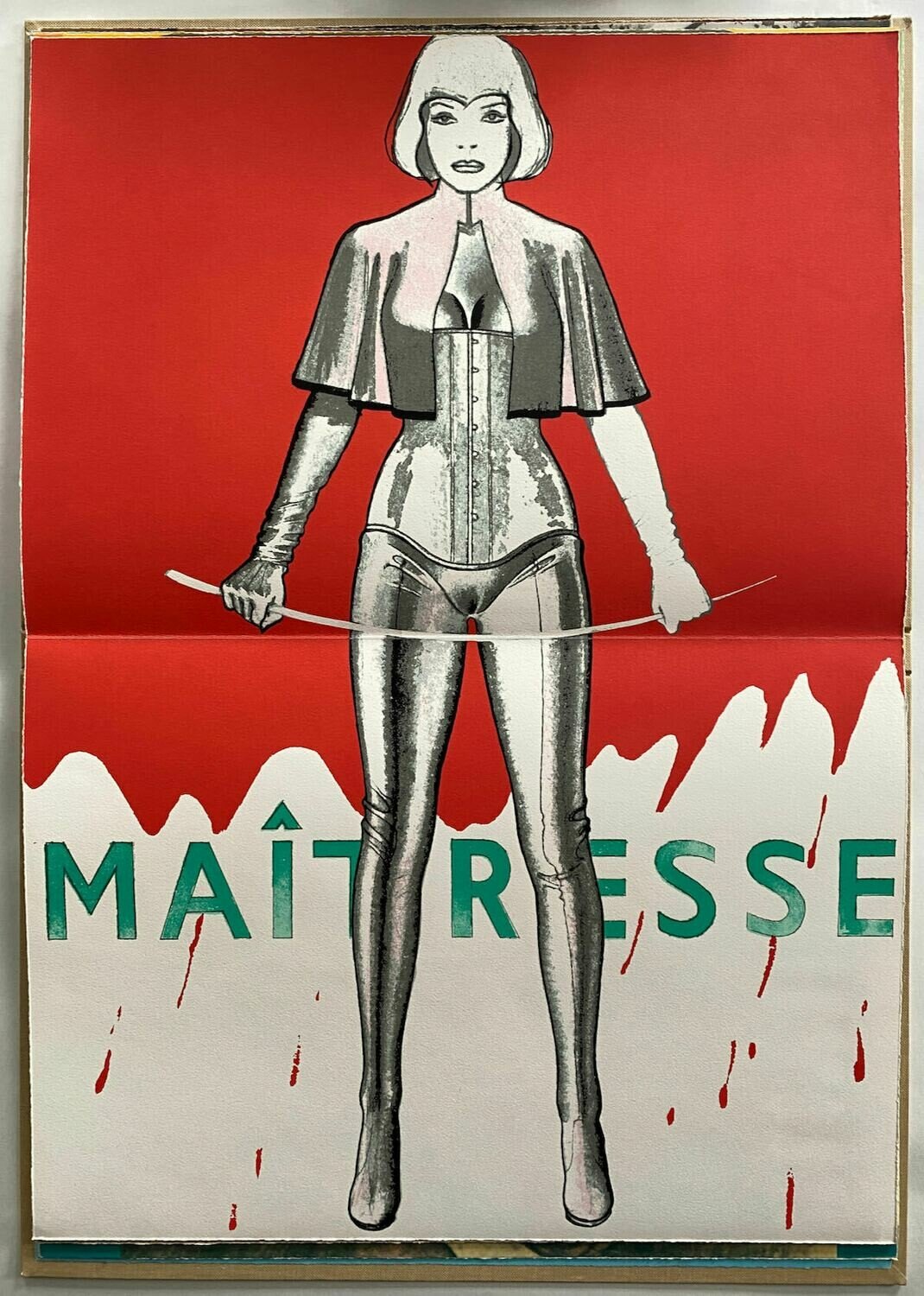

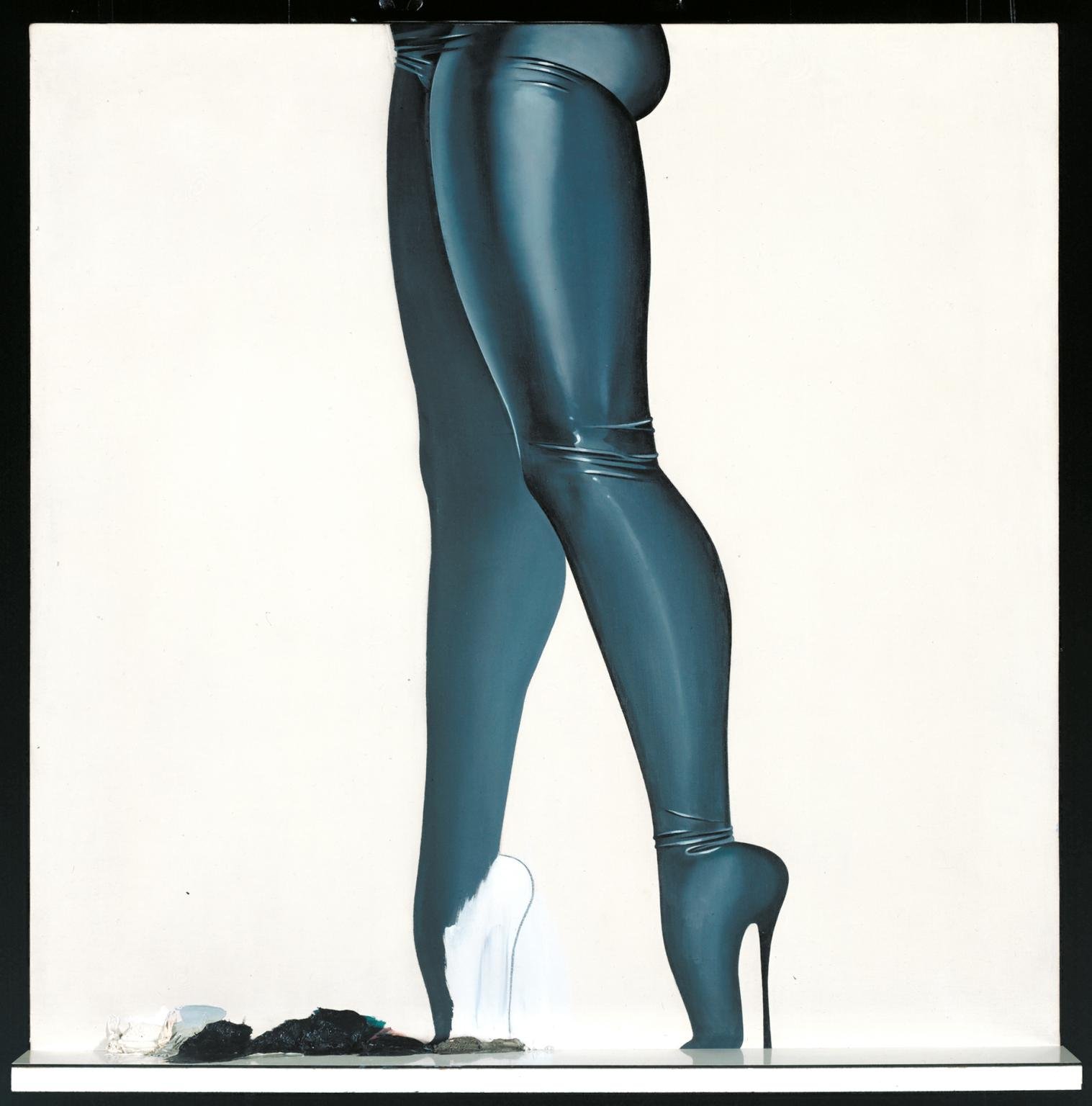

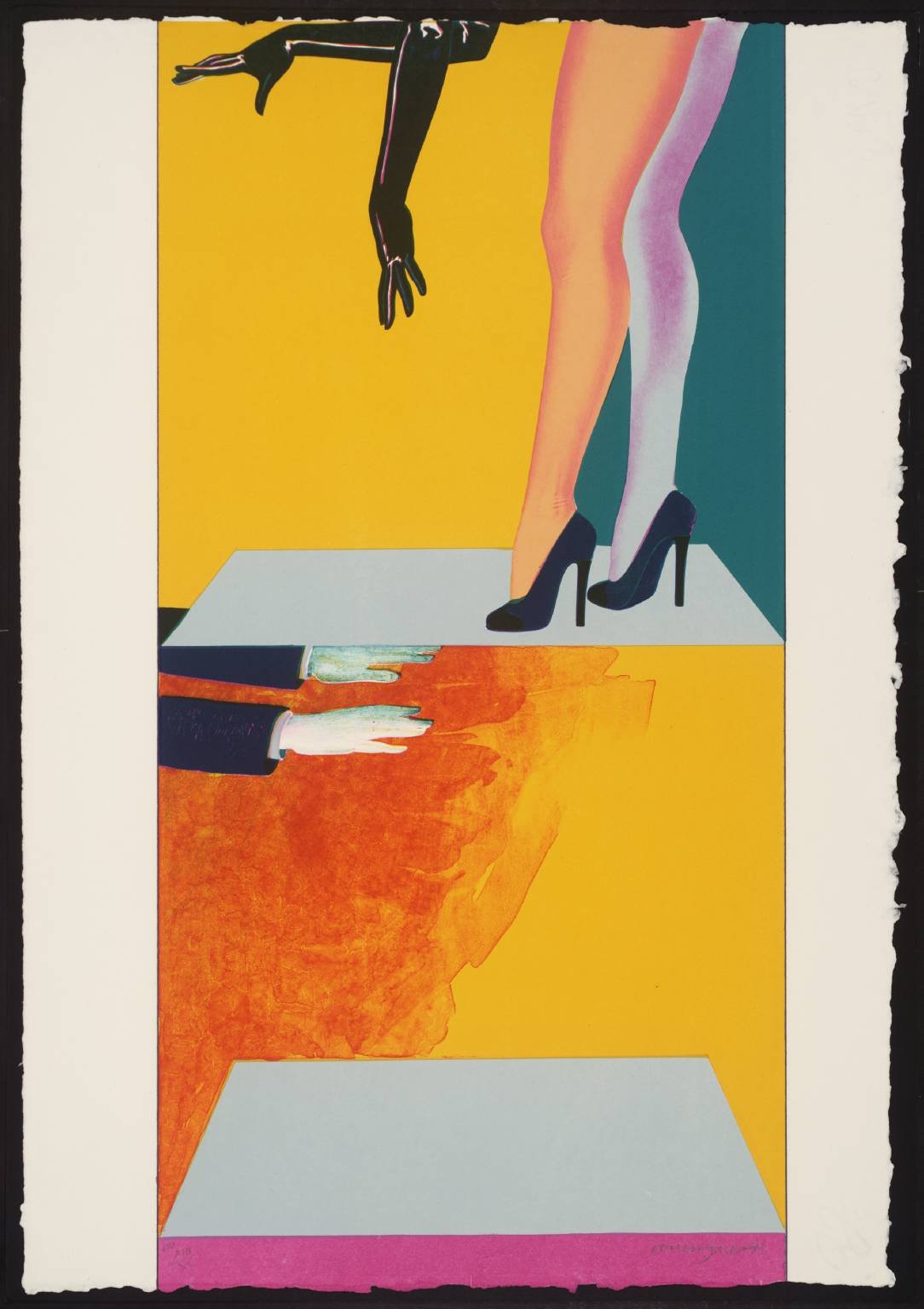

Allen is known for his brightly coloured paintings, prints and sculptures often of the female form, riffing on fetish imagery. He became famous—or maybe rather infamous—for his 1969 sculptures of pneumatic female mannequins as furniture: a chair, a hat stand, and a table. These provocative sculptures caused an uproar, with feminists widely decrying them as misogynistic. This backlash still lingers today (as seen with this 2014 Guardian headline, “Is Allen Jones’s sculpture the most sexist art ever?”), yet Allen’s work is much more than just the erotic.

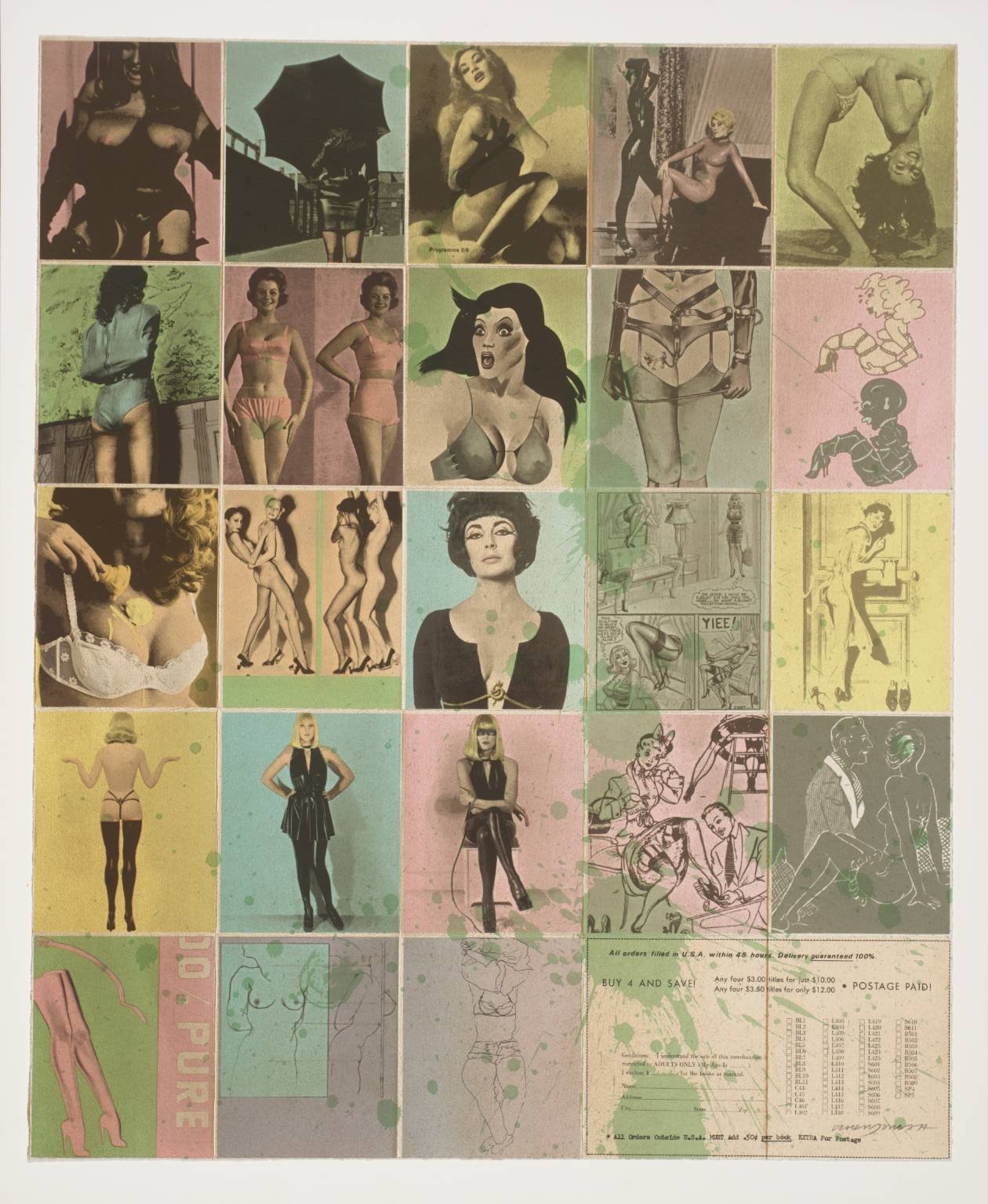

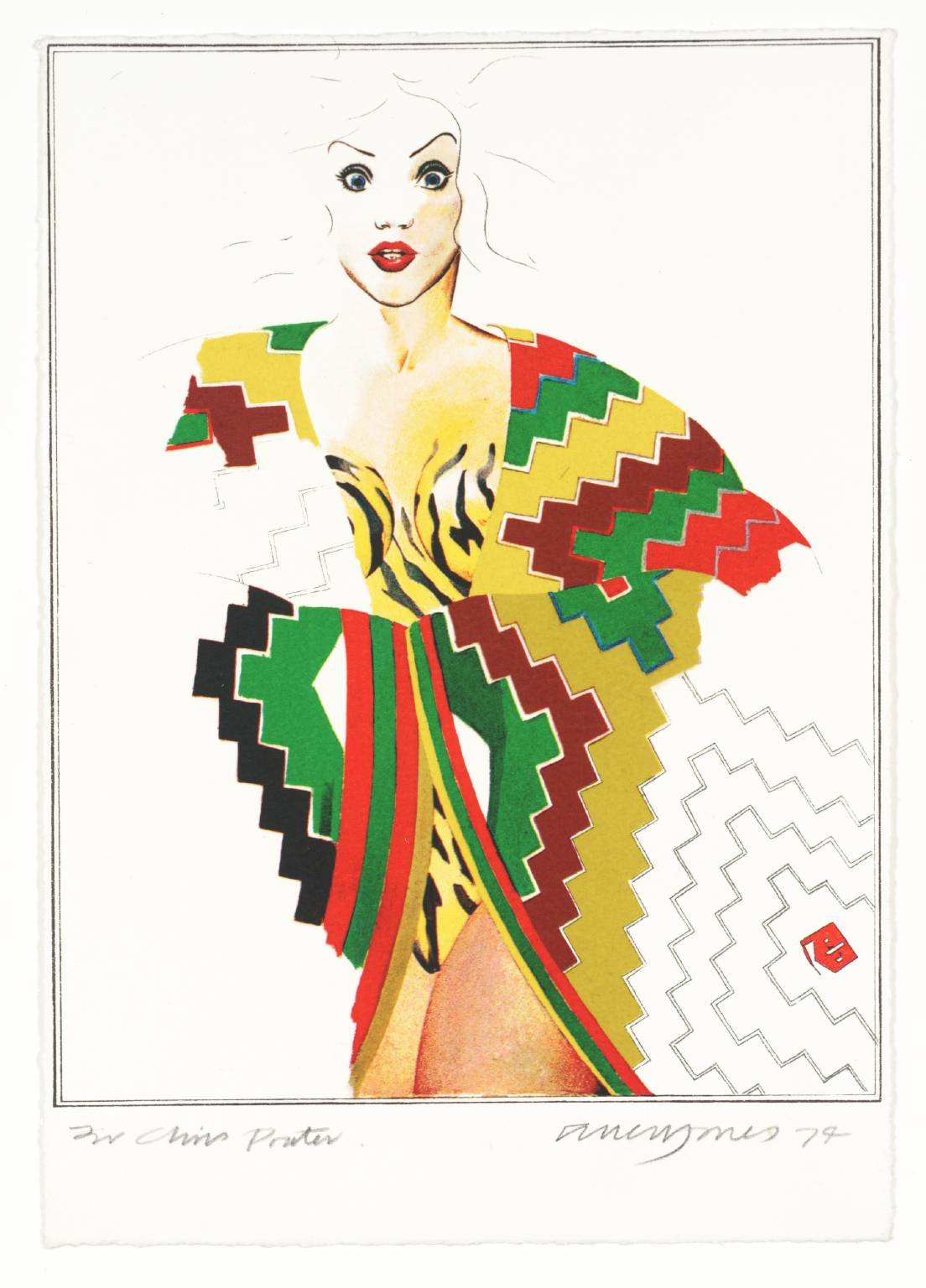

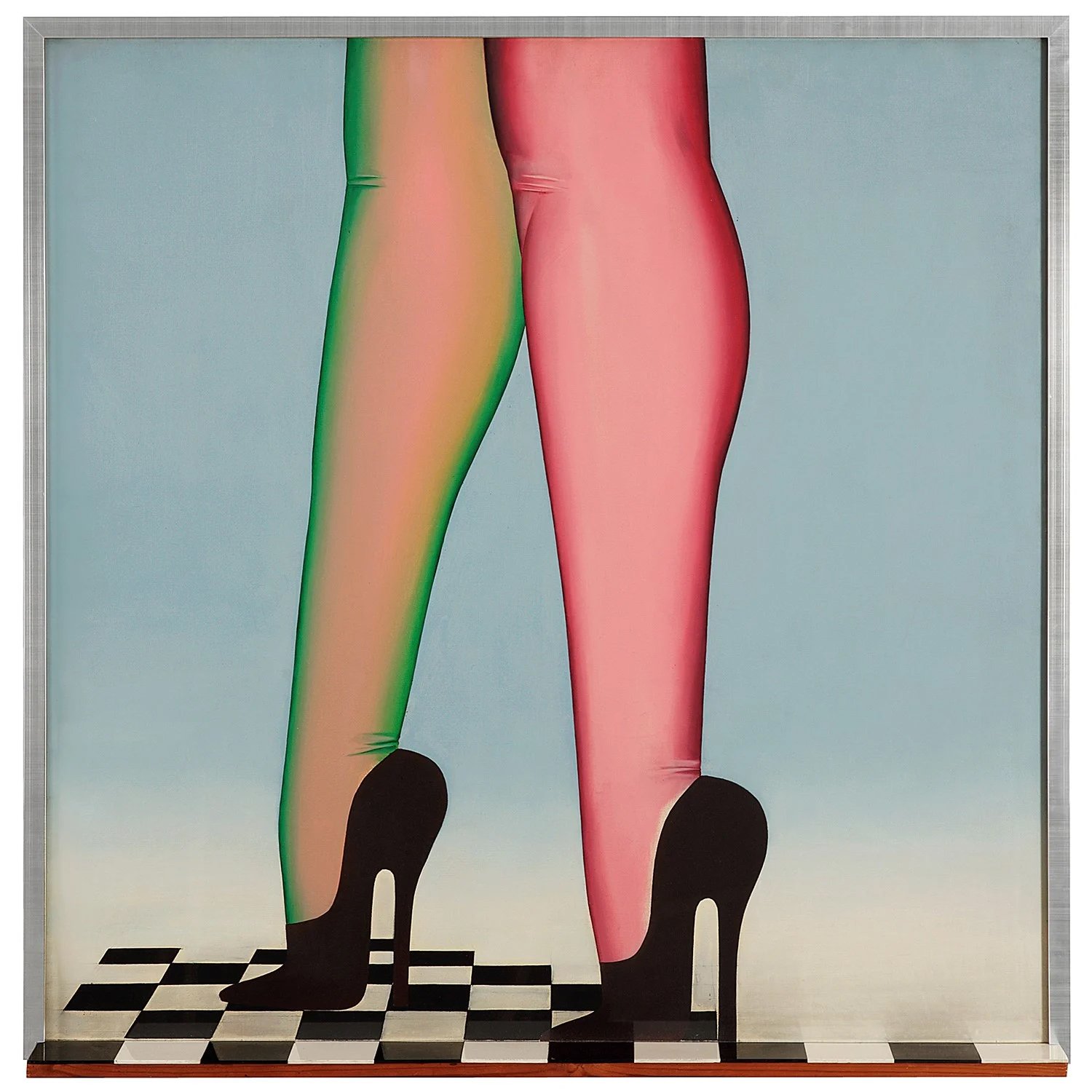

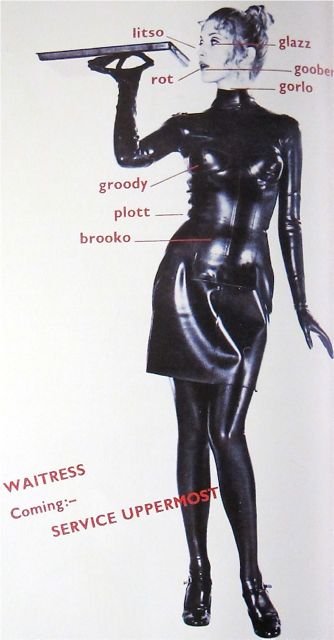

“Jones’s paintings are not clinical examinations of a fetish for rubber or leather; rather, these highly tactile materials fulfill a valuable function in stressing the surface of the picture and in encouraging an immediate and physical response from the viewer. Neither are the paintings indicative of a lecherous taste for female legs, cleavage or the rather more specialized attachment to shoes with stiletto heels. This concentration on a select range of forms arises from their value as standardized symbols, as a means of gaining access to a universal idea through the more directly comprehended example from the material world. Jones’s work is sexually-derived, but its erotic substance lies not so much in specific images as in the contemplation of the mystery of sex and creation.”

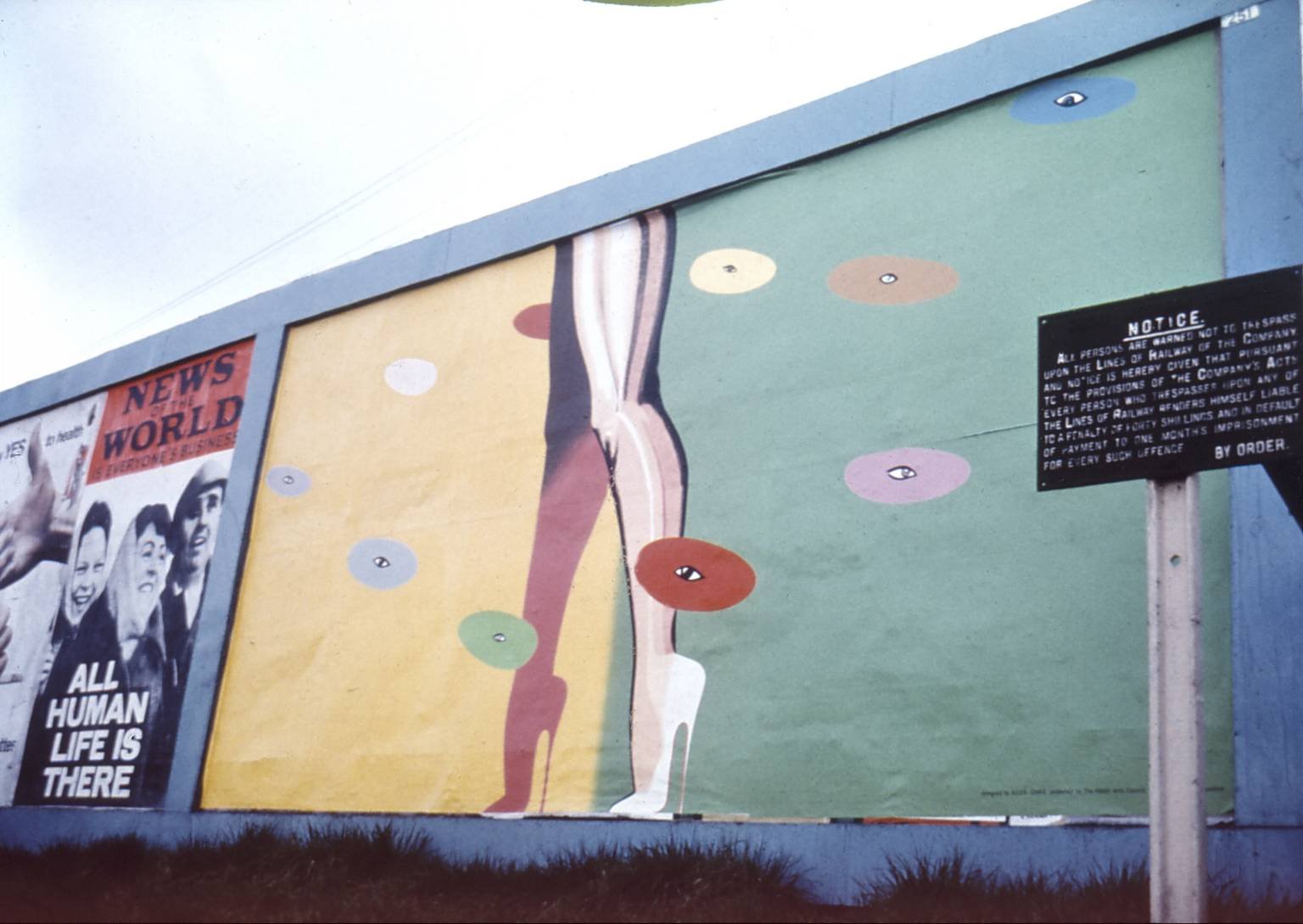

Allen was born in Southampton in 1937 and grew up in the London suburbs. Allen studied painting and lithography at Hornsey College of Art between 1955 and 1959, after which he entered the Royal College of Art alongside what was to become the first generation of British pop artists: RB Kitaj, David Hockney, Peter Phillips and Derek Boshier. Vitally moving art forwards, they became known at the Royal College as a group of troublemakers; at the end of their first year, Jones was expelled as an example to the rest of them. He returned to the Hornsey College of Art to take a Teacher Training Course after which he taught lithography at Croydon College of Art, then drawing at Chelsea School of Art. In 1964 he moved to New York with his first wife and lived for a year at the Chelsea Hotel, before going on an extended tour of the United States by car. While his early work had been more abstract, Allen’s time in America helped him develop a more hard-edged painting style while also introducing him to fetish imagery. After his return to the UK, Allen settled with his family in London and began refining his new vision.

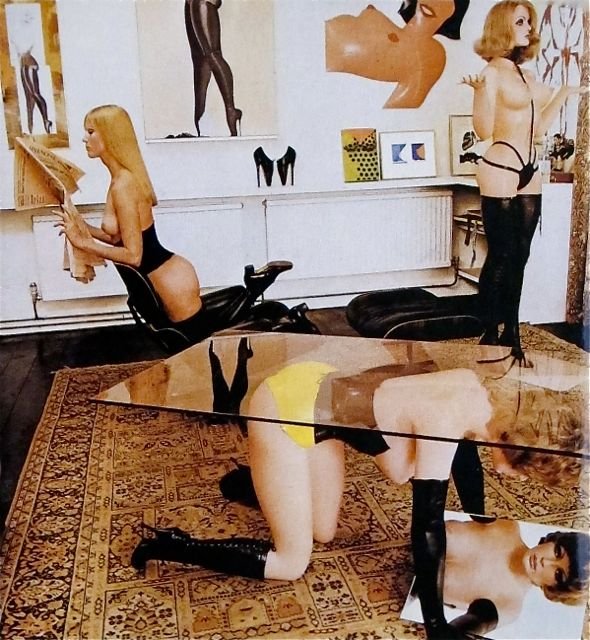

Allen Jones’ infamous furniture sculptures:

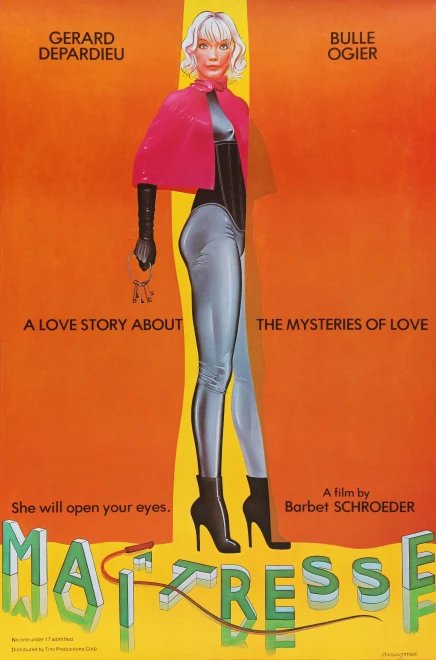

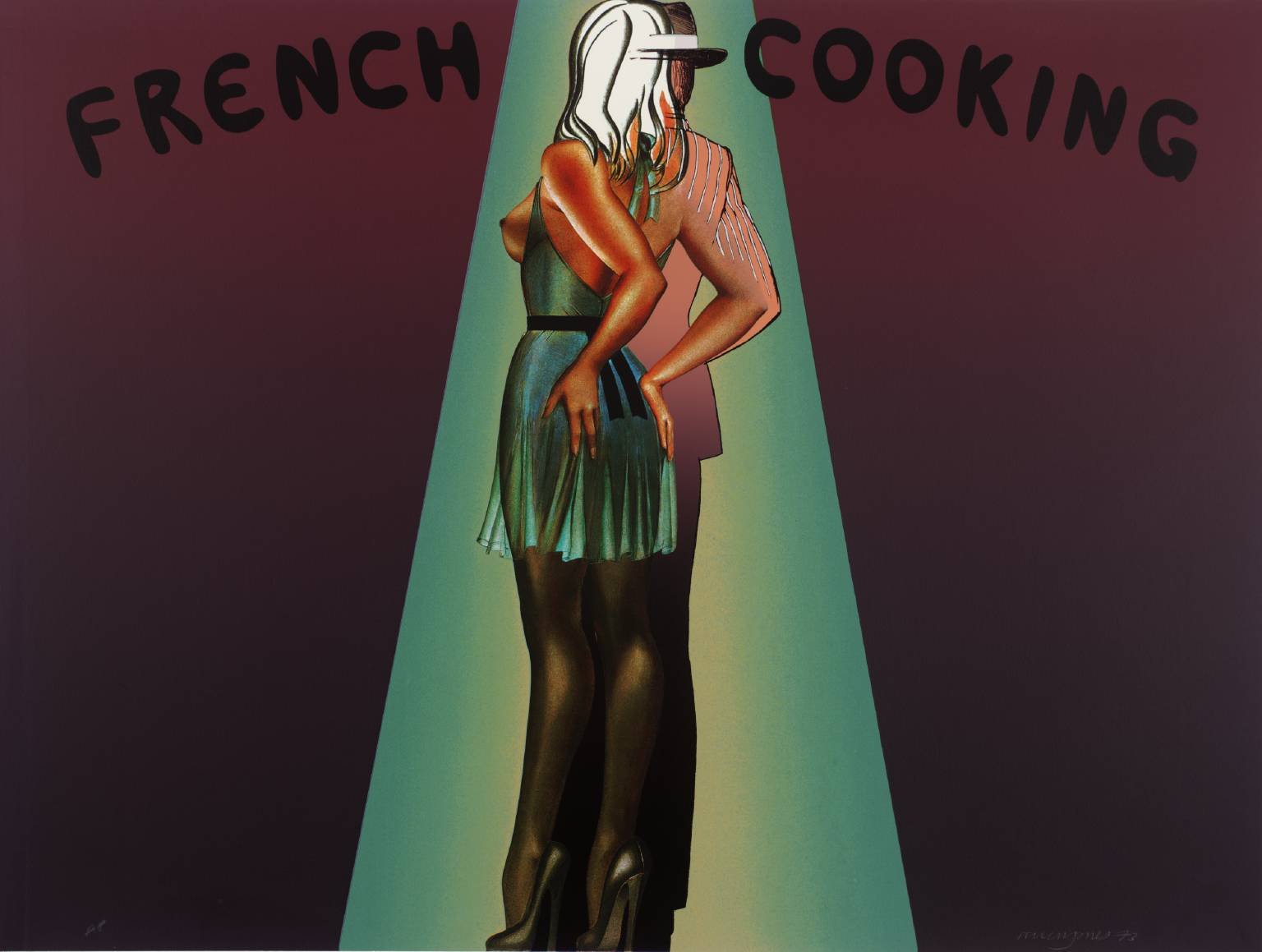

Though originating from fetish catalogue imagery, Jones’ images and sculptures of women have in turn been so influential that it has been said that “almost no image of woman-as-object or woman-as-other-object can be created, even 40 years later, that doesn’t nod to them.” Such is the impact that Allen even put together a book of copies from across art, editorials and advertising—from Stanley Kubrick (who wanted Jones to work on A Clockwork Orange for free and then made riffs of his tables for the Korova Milkbar) to Steven Klein (who photographed Kylie Jenner for Interview as Jones’ table).

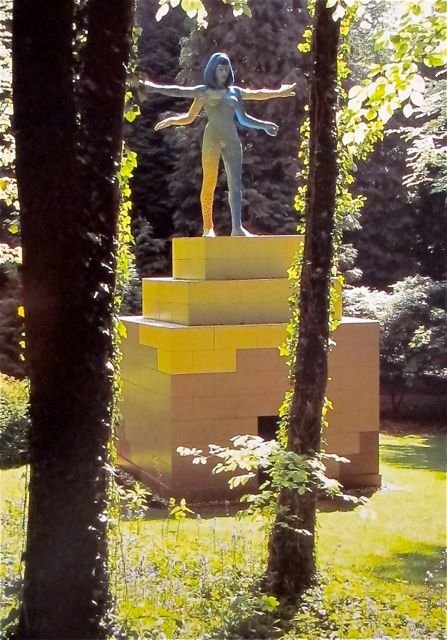

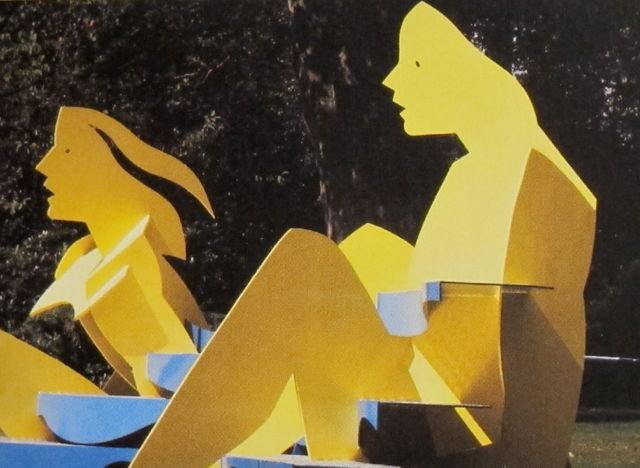

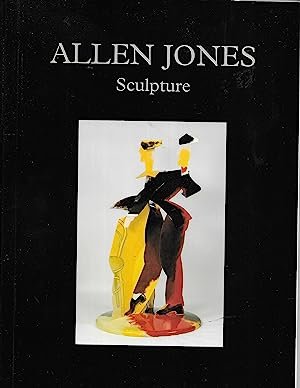

A masterful painter, Jones combines graphic hard edges with washes of luminous colour and expert modeling of flesh and textile. From the beginning of his career there was an impulse towards three dimensions—first with shaped canvases, then objects projecting off them, before he began creating sculptures. Beyond his mannequins, Allen’s sculptures from the 1980s to today take from the 2D and fold it into 3D—line drawings of dancers or an acrobat truly move through space, flat form folding over flat form in sensuous action. As Charles Jencks remarked, it's “provocation through whirling movement, suggestion and vital color.” In recent years, Jones has begun to incorporate movement in a new way—while I was at his studio I saw a new work that includes a moving digital avatar of the “Hat Stand” sculpture; last year, one of the sculptures walked a screen the length of a room in an exhibition curated by Christian Louboutin.

Allen’s Oxfordshire studio. Photos by Eamonn McCabe for the Royal Academy:

“The Acrobat,” 1993, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital.

Though I had a huge list of subjects to cover, the majority of our conversation focused on that year in New York, his trip around the United States, his first time in Los Angeles, and the huge impact that trip had on his work—from his introduction to fetish imagery to the development of a more hard-edged painting style. We also cover his more recent work and how the pandemic led Allen and his wife to move to the countryside full-time. I’d like to thank Joan Quinn for connecting us—you can go back to episode 32 to listen to my conversation with her.

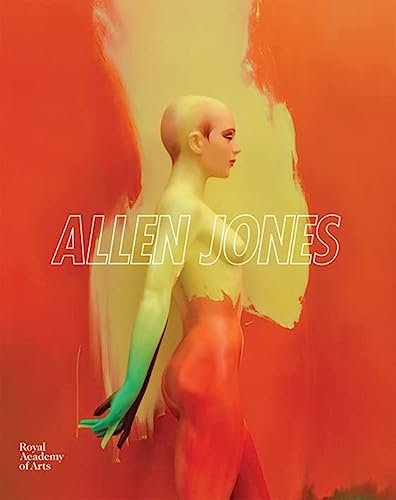

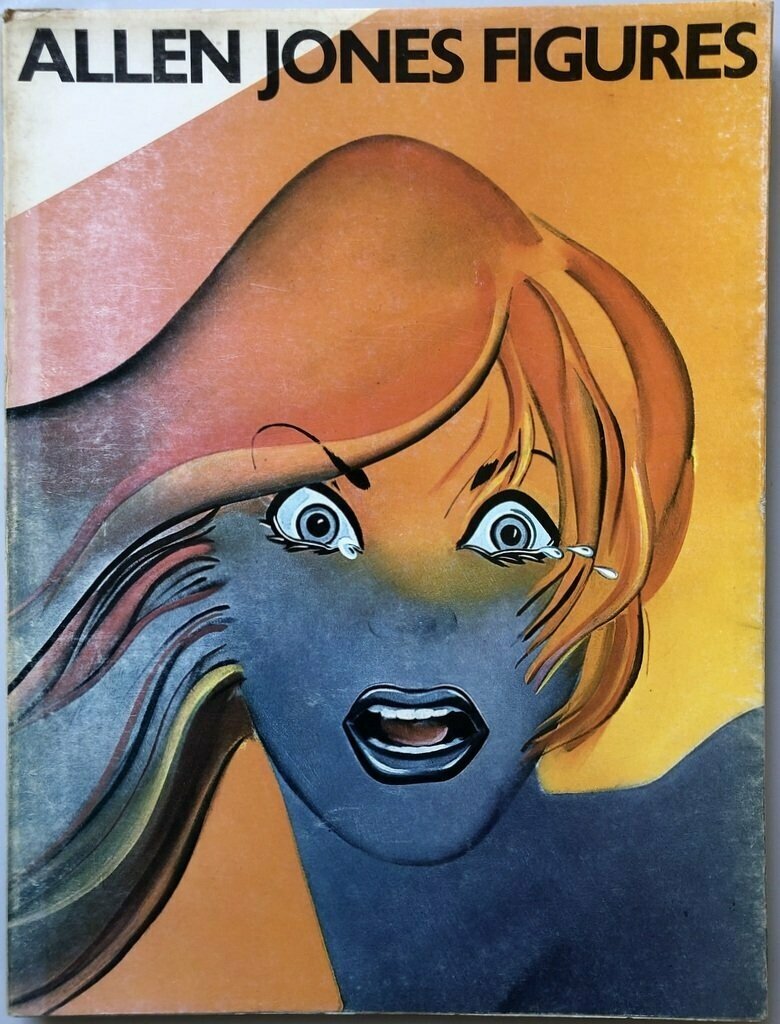

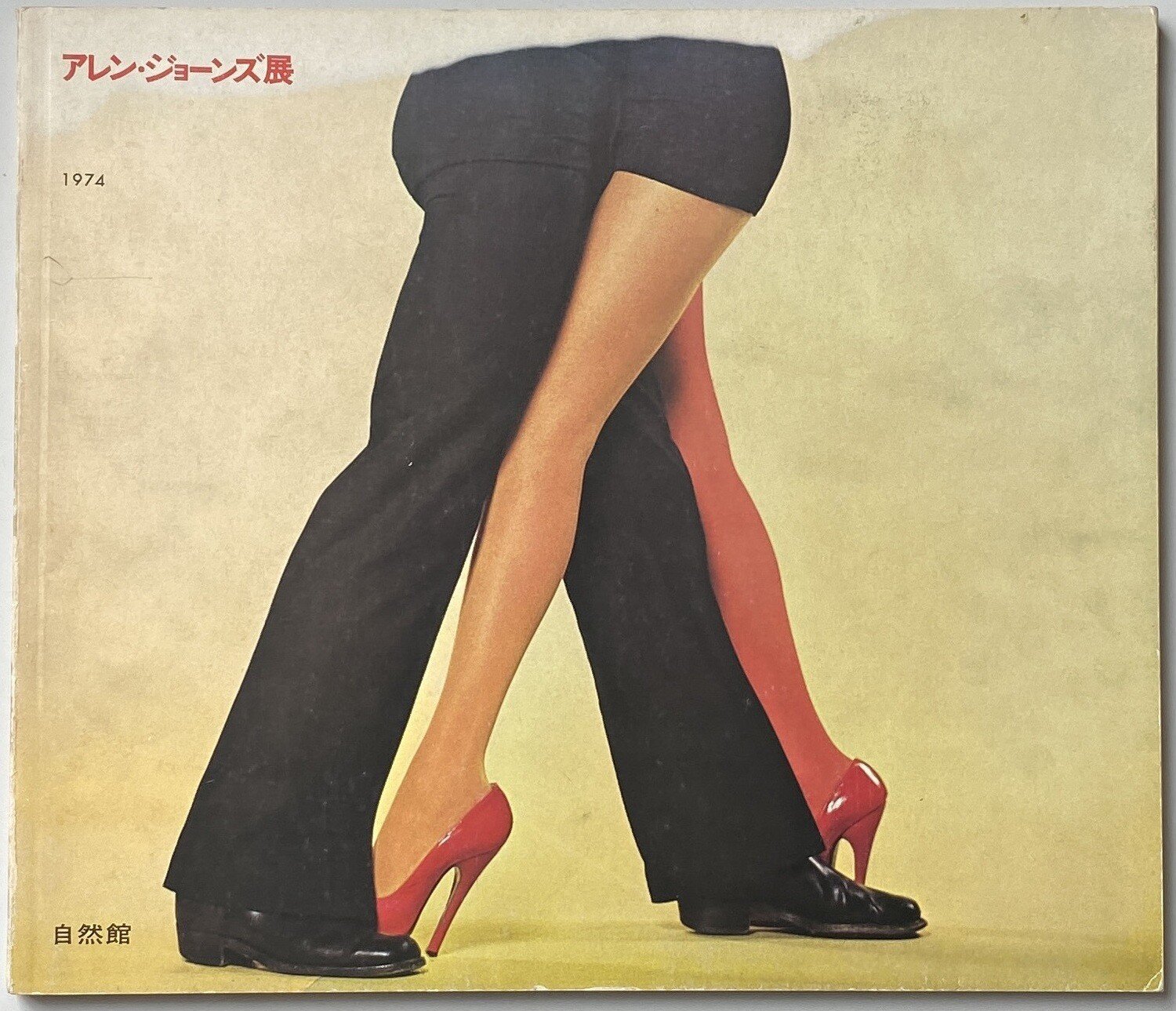

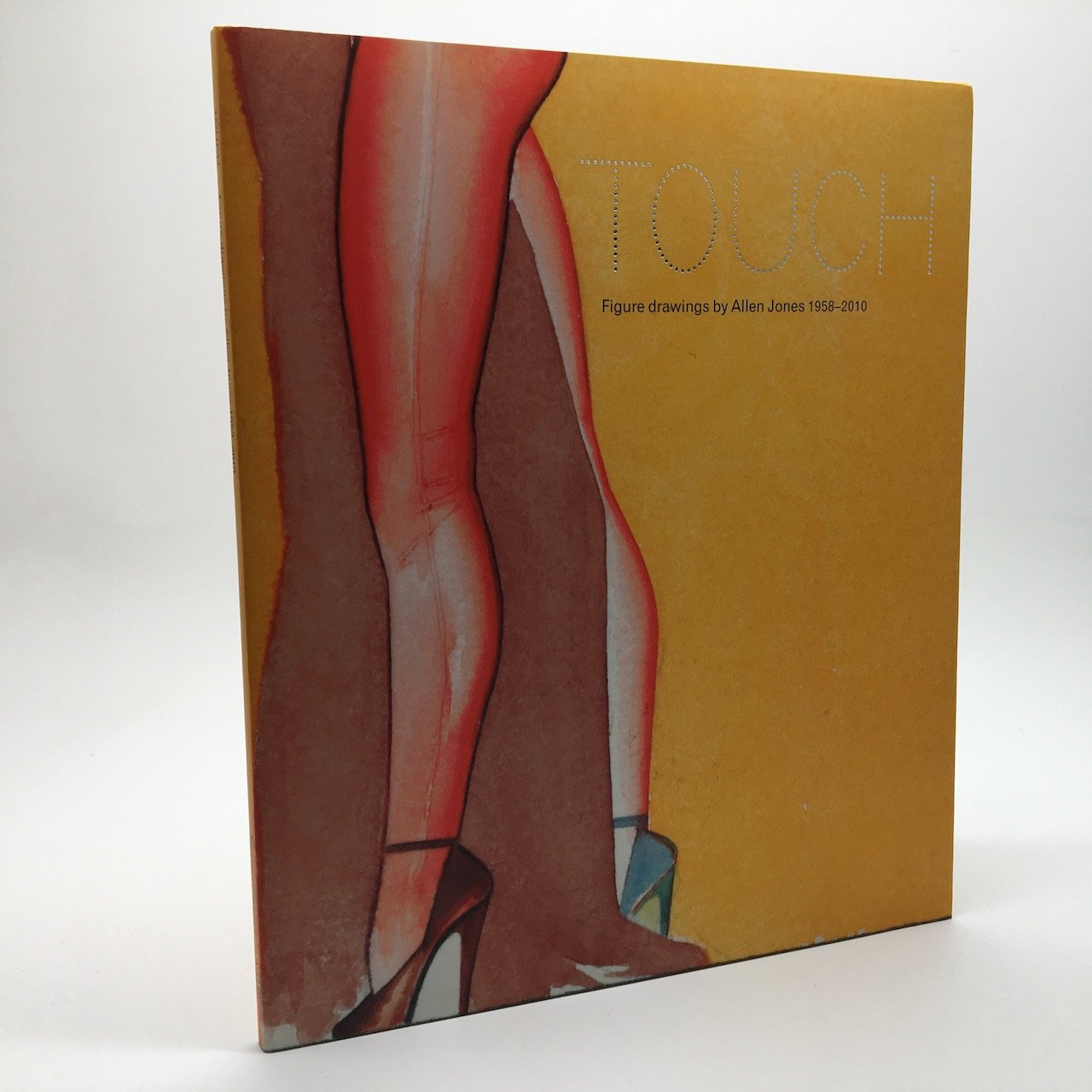

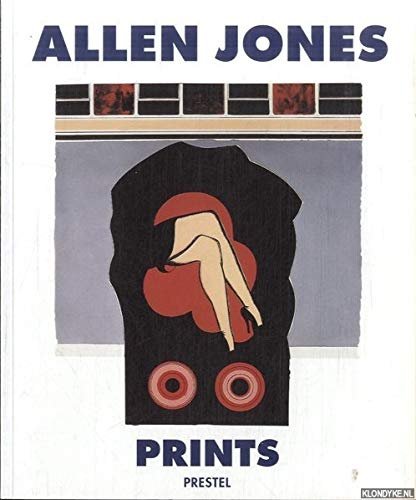

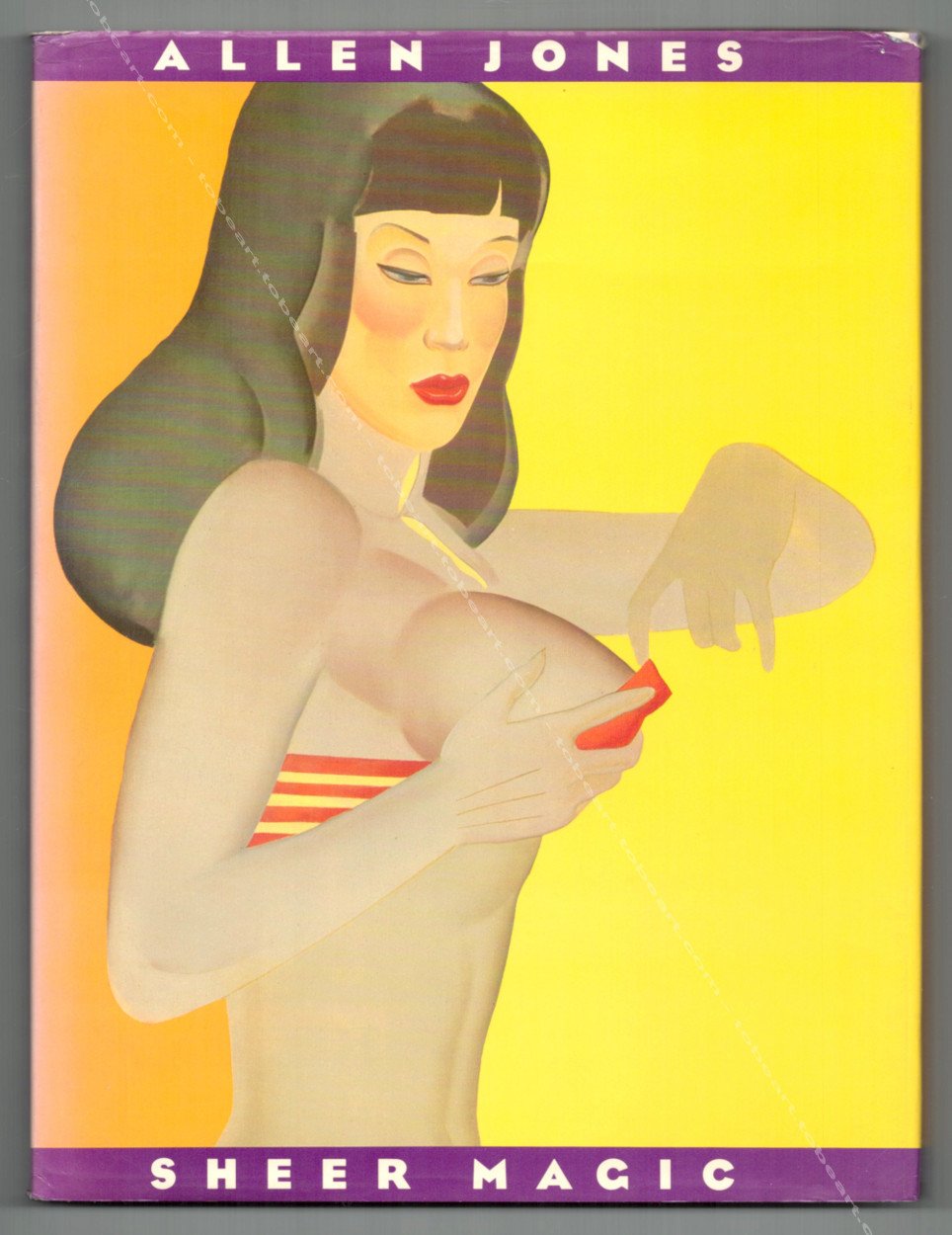

With such a long and illustrious career, it is unsurprising that there have been many books and exhibition catalogues published about Allen’s work—hopefully, this conversation whets your appetite to learn more about him.

![Allen Jones [no title] 1976–7 .jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/609a8352ee3ff81d507b3890/1688945475632-L4GQI0NPO76PCMZSU3KM/Allen+Jones+%5Bno+title%5D+1976%E2%80%937+.jpg)